In August, an armada of 230 chinese fish boats, accompanied by 7 taiwanese Coast Guard ( CCG ) vessels, was spotted near the Senkakus. This could have led to a nightmare scenario for Tokyo in which the disputed islands are seized by Chinese armed fishermen. Such a situation could promptly escalate with the catch of the intruders at ocean by the Japan Coast Guard ( JCG ) or on farming by the police forces, followed by the deployment of Chinese naval vessels to rescue its citizens. The Japan Maritime self-defense Forces ( JMSDF ) could then be deployed on web site, on the request of the Cabinet Office, lone with limited authority to use coerce ( law-enforcement powers ). This chain of events would create a tense repulsion between JMSDF and Chinese naval vessels with a high gear gamble of developing into a military incident. The dilemma for Japan would be to choose between being the foremost side to use wedge to displace the intruders and leaving them alone with the risk of Beijing claiming actual operate of the islands. In this kind of scenario, a clear division of roles between the JCG and JMSDF, with the early participation of the latter, would ensure a greater deterrence effect and a fleet and coherent response in case of an trespass .

The JCG is a civilian law-enforcement means that was created in 1948 after the U.S. Coast Guard model. Its police missions have increasingly touched on national security issues as incursions into japanese waters, particularly by north korean and taiwanese governmental vessels and fishing boats, become more frequent. Since 2000, the JCG has been allowed, under certain conditions, to stop leery ships with target fire. This led some experts, such as Richard Samuels, to describe the JCG as a “ fourth branch of the japanese military. ” however, even today, the status, mission, budget, and capacities of the JCG are still distinctly distinct from those of the JMSDF. indeed, the JMSDF has a budget of 1,200 billion yen ( $ 9.9 billion ), which is over five times the size of the JCG ’ randomness budget, and includes 45,500 personnel ( compared with 13,422 for the JCG ) to defend Japan ’ s maritime world and engage in noncombatant operations oversea. consequently, the JMSDF patrols japanese waters with vessels and airplanes and replies to warship intrusions. It besides supports the JCG when the latter can not adequately respond to contingencies .

In gray-zone situations, civilian or paramilitary forces are used to change facts on the crunch while taunting the aim country to finally use military unit to halt these activities. such tactics, which do not amount to an armed attack, have been identified by Tokyo as a threat since 2010 and have informed the transformation of Japan ’ s defense mechanism position. The politics is organizing a “ dynamic joint defense impel ” and has redeployed troops onto the Ryukyu Islands, on the southwest of the archipelago close up to the Senkakus. furthermore, official documents are calling for more cooperation and coordination between the JMSDF, on the one hand, and the JCG and patrol forces, on the other, which until recently have been isolated from one another despite playing complemental maritime roles.

In gray-zone situations, civilian or paramilitary forces are used to change facts on the crunch while taunting the aim country to finally use military unit to halt these activities. such tactics, which do not amount to an armed attack, have been identified by Tokyo as a threat since 2010 and have informed the transformation of Japan ’ s defense mechanism position. The politics is organizing a “ dynamic joint defense impel ” and has redeployed troops onto the Ryukyu Islands, on the southwest of the archipelago close up to the Senkakus. furthermore, official documents are calling for more cooperation and coordination between the JMSDF, on the one hand, and the JCG and patrol forces, on the other, which until recently have been isolated from one another despite playing complemental maritime roles.

WHY IS THERE NO LEGAL STRUCTURE FOR COOPERATION BETWEEN THE JCG AND THE JMSDF?

The motion of coping with gray-zone situations was supposed to lie at the core of the security legislation passed by the Shinzo Abe politics in September 2015. however, the series of laws ultimately adopted did not directly address the issue but rather focused on the limited use of the correct of collective self-defense .

In 2014 the Abe government actually discussed formulating a legal placement to help redefine the respective responsibilities of the patrol, JCG, and JMSDF when dealing with gray-zone situations in order to ensure smooth interagency cooperation during peacetime. These negotiations did not lead to legislation, however, chiefly because of the contest between agencies to protect their respective missions. In particular, the JCG, a strictly civilian agency according to Article 25 of the Japan Coast Guard Law, resisted expanding its deputation to encompass more “ paramilitary ” activities. political reasons besides played a function in the decision to shelve the legal option, as the New Komeito ( a junior member of the ruling coalition ) argued that most gray-zone scenarios could be handled by the JCG using law-enforcement measures alone .

In 2014 the Abe government actually discussed formulating a legal placement to help redefine the respective responsibilities of the patrol, JCG, and JMSDF when dealing with gray-zone situations in order to ensure smooth interagency cooperation during peacetime. These negotiations did not lead to legislation, however, chiefly because of the contest between agencies to protect their respective missions. In particular, the JCG, a strictly civilian agency according to Article 25 of the Japan Coast Guard Law, resisted expanding its deputation to encompass more “ paramilitary ” activities. political reasons besides played a function in the decision to shelve the legal option, as the New Komeito ( a junior member of the ruling coalition ) argued that most gray-zone scenarios could be handled by the JCG using law-enforcement measures alone .

The case for a legal arrangement was subsequently raised by the opposition parties. In summer 2015, the Democratic Party of Japan and the Japan Innovation Party jointly proposed a “ territorial security bill ” ( ryoiki keibi hoan ) defining precedence zones in the East China Sea in which the JMSDF would assume primary coil province for patrols and defense. Yet this bill was rejected on the grounds that it would have the consequence of pinpointing the weaknesses, or “ voiced bellies, ” in Japan ’ s territorial refutation. In the absence of a legal framework, there have been many calls for greater operational coordination between police, the JCG, and the JMSDF .

The second question related to legal issues and procedures is the nature of JMSDF interposition in gray-zone situations. When the JCG can not manage a gray-zone situation, the JMSDF can be sent in for support. In such cases, as no proper military attack has taken position, the JMSDF does not take “ orthodox military action ” ( boei kodo ). rather, it conducts “ nautical security operations ” ( kaijo keibi kodo ) in hold of the JCG according to Article 82 of the Self-Defense Forces Law. Under this decree, the JMSDF can use weapons under the rigid conditions outlined in the JCG Law. To date, such an ordain has been issued by the Prime Minister ’ mho Office alone three times : in 1999 to chase a suspected north korean descry transport, in 2004 in response to the incursion of a chinese submarine in japanese territorial waters, and in 2009 to allow the JMSDF to conduct antipiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden .

This specific order follows from the characteristics of Japan ’ s defensive structure policy : the missions and activities conducted by the Japan self-defense Forces ( JSDF ) are described in a positivist list, which is much more restrictive than the negative tilt that limits most other countries ’ military activities. While the japanese government considers maritime security operations to be another layer of law-enforcement operations conducted by more capable forces to prevent a military escalation, China does not share this sympathy and would consider any intervention of the JMSDF in a gray-zone position as a unilateral military escalation by Japan. That is why China ’ s scheme of “ reactive assertiveness ” presents such a challenge : Japan must respond to a gray-zone position using a black-and-white security system in which optimum coordination between the JCG and JMSDF is difficult to achieve. The government however tried to facilitate the operation to ensure a smooth response by the JSDF, if needed. Since May 2015, only a earphone call from the Cabinet Office is needed to authorize intervention by the JSDF. however, some experts and practitioners believe that the rules of engagement under Article 82 of the Self-Defense Forces Law may not be broad enough to retake control of the situation in a gray-zone emergency, nor even have a real deterrent effect .

This specific order follows from the characteristics of Japan ’ s defensive structure policy : the missions and activities conducted by the Japan self-defense Forces ( JSDF ) are described in a positivist list, which is much more restrictive than the negative tilt that limits most other countries ’ military activities. While the japanese government considers maritime security operations to be another layer of law-enforcement operations conducted by more capable forces to prevent a military escalation, China does not share this sympathy and would consider any intervention of the JMSDF in a gray-zone position as a unilateral military escalation by Japan. That is why China ’ s scheme of “ reactive assertiveness ” presents such a challenge : Japan must respond to a gray-zone position using a black-and-white security system in which optimum coordination between the JCG and JMSDF is difficult to achieve. The government however tried to facilitate the operation to ensure a smooth response by the JSDF, if needed. Since May 2015, only a earphone call from the Cabinet Office is needed to authorize intervention by the JSDF. however, some experts and practitioners believe that the rules of engagement under Article 82 of the Self-Defense Forces Law may not be broad enough to retake control of the situation in a gray-zone emergency, nor even have a real deterrent effect .

RECENT MOVES TO CLOSE THE OPERATIONAL GAP

Because the JCG and JMSDF are different in nature, there has not historically been a culture of close cooperation and coordination between the two institutions. however, this has gradually changed, specially after the episodes in 1999 and 2001 when union korean spy boats entered territorial waters. The JCG and JMSDF subsequently adopted a manual to set up procedures for joint responses to such scenarios and engaged in joint aim. Another important step toward improving people-to-people relations was the government ’ randomness decision to allow JCG officers onboard JMSDF ships to conduct antipiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. such cooperation has been ongoing since 2009. In July 2015, the two forces held their first gear joint educate on a gray-zone scenario, although the drill was limited to law-enforcement activities. More recently, on November 11, the JSDF, JCG, and police forces conducted their first base roast drill to cope with illegal submission of arm fishermen on a distant island. Another factor that has improved reciprocal sympathy between JCG and JMSDF counterparts is the evolution of the JCG ’ s government since 2013 to allow officers, alternatively of civilians from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism ( MLIT ), to hold the circus tent post of commanding officer .

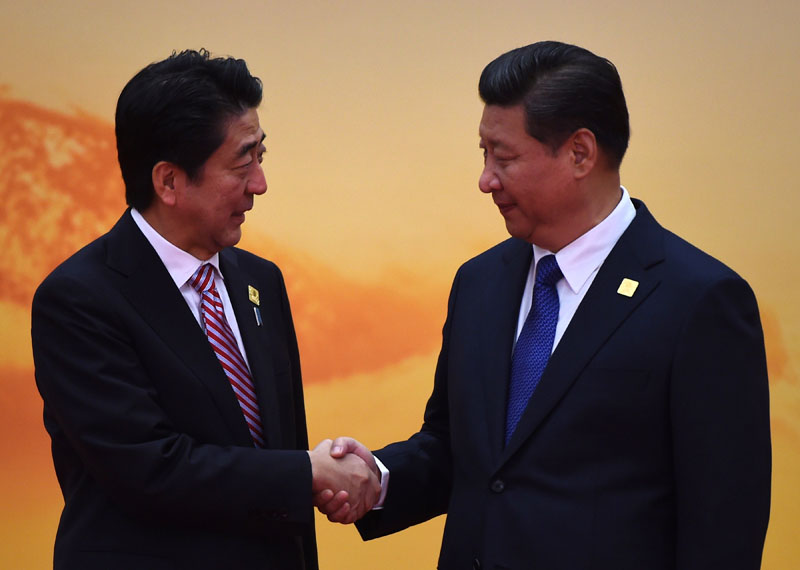

In summation, the JCG and JMSDF have adopted an information-sharing protocol and immediately exchange information on a daily footing between the two corporation. They are besides setting up a model for coordination both at the operational level and between regional commands. This framework has helped manage Japan ’ s daily interactions with chinese boats around the Senkakus. Since October 2013, and more resolutely November 2014, when Abe and Xi Jinping agreed to meet, the situation has been stabilized by the relative routinization of interactions between the two coast guards according to a 3-3-2 formula : three CCG ships enter japanese waters three times a month for up to two hours each visit. however, since the sequence of the Chinese fleet passing near the Senkaku Islands final summer, the CCG ’ sulfur everyday seems to have changed to a 4-3-2 formula : four ships have been spotted three times a calendar month in Japan ’ s territorial waters, lingering for up to two hours .

As they observe the developments in the South China Sea, japanese officials are anxious about the hypothesis of a future coup de storm, specially as CCG capacity is growing at a rapid pace. From this position, the current tied of coordination between the JCG and JMSDF is calm not high enough and many challenges to deepening cooperation stay.

As they observe the developments in the South China Sea, japanese officials are anxious about the hypothesis of a future coup de storm, specially as CCG capacity is growing at a rapid pace. From this position, the current tied of coordination between the JCG and JMSDF is calm not high enough and many challenges to deepening cooperation stay.

Read more: A Man Quotes Maritime Law To Avoid Ticket

NEXT STEPS FOR CLOSER COOPERATION

According to japanese experts on nautical law enforcement, the JCG and JMSDF could take a number of steps to improve collaboration. First, they could update their communication systems and secure channels. As identified in 2011, civilian and military units typically do not use the lapp equipment to communicate. The hardware, software, and procedures of the JCG are peculiarly outdated when compared with the JMSDF ’ randomness systems .

second, the two fleets do not plowshare technology for nautical world awareness ( MDA ), which limits their setting for coordination and prevents prediction and sympathy of a deteriorating position. Sharing this technology would allow for fully integrated, comprehensive MDA .

Third, a common incorporate C4ISR ( command, dominance, communication, computer, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance ) system is being developed to serve the three branches of the JSDF ( Ground, Maritime, and Air ). Plans should be made for a like JCG upgrade .

fourth, the JCG and JMSDF need to engage in more articulation exercises and train to ensure smooth joint operations should a gray-zone situation worsen. One important challenge to address is that the JCG and JMSDF do not share a chain of command and control .

Another measure for consideration would be the consolidation of the JCG within the security government institutions. As character of the MLIT, the JCG is represented to a certain extent in the National Security Council, but its association with the alliance coordination mechanism with U.S. forces is still under discussion .

finally, most experts and practitioners concur that Japan needs to replace existing JCG boats with more modern ships. Estimates suggest that around 35 % of the 366 JCG patrol boats, built in the 1970s and 1980s, are outdated. furthermore, 50 % of the JCG ’ s ships will need replacing in the following five years. In April 2016 a budget was passed to replace 15 % of the outdated vessels, but in the years to come shipbuilding must accelerate—a job that could be outsourced with discriminatory conditions to Japan ’ s maritime partners in Southeast Asia .

finally, most experts and practitioners concur that Japan needs to replace existing JCG boats with more modern ships. Estimates suggest that around 35 % of the 366 JCG patrol boats, built in the 1970s and 1980s, are outdated. furthermore, 50 % of the JCG ’ s ships will need replacing in the following five years. In April 2016 a budget was passed to replace 15 % of the outdated vessels, but in the years to come shipbuilding must accelerate—a job that could be outsourced with discriminatory conditions to Japan ’ s maritime partners in Southeast Asia .

A thorough discussion should take set regarding the fundamental motivation for Japan to adopt a “ whole of government ” approach to regional security system. indeed, improving the area ’ s current security model depends much more on implementing such an set about than on revising Article 9 of the japanese united states constitution. Breaking down bureaucratic stovepipes to create a culture of coordination is no comfortable task and has met with ferocious resistance not entirely in Japan but in numerous early countries. The preceding discussion has identified several steps that Japan could take to begin this summons of improving cooperation between the JCG and the JMSDF .

Céline Pajon is a Research Fellow at the Center for asian Studies in the Institut français des relations internationales ( Ifri, or the french Institute of International Relations ).

This MAP Analysis was a preview of the writer ’ mho article “ Japan ’ s Coast Guard and Maritime Self-Defense Force in the East China Sea, ” subsequently published in Asia Policy .

Download a pdf interpretation of this analysis piece here .

Banner effigy : © Ted Aljibe/AFP/Getty Images. japanese Coast Guard ship PLH02 Tsugaru is seen past a cargo vessel during an exert off Manila Bay on July 13, 2016 .