The economy of the Song dynasty ( 960–1279 ) in China was the early mod world ‘s most comfortable. The dynasty moved away from the top-down command economy of the Tang dynasty ( 618-907 ) and made across-the-board use of market mechanisms as national income grew to be around three times that of 12th century Europe. The dynasty was beset by invasions and border coerce, lost control condition of North China in 1127, and fell in 1279. Yet the time period saw the growth of cities, regional specialization, and a national market. There was free burning growth in population and per caput income, morphologic change in the economy, and increased technical invention. movable print, improved seeds for rice and early commercial crops, gunpowder, water-powered mechanical clocks, the consumption of coal as an industrial fuel, improved cast-iron and steel product, more effective canal locks, were alone the most significant technical innovations. Commerce in ball-shaped markets increased importantly. Merchants invested in trade vessels and trade which reached ports as far aside as East Africa. This period besides witnessed the development of the world ‘s first bill, or printed composition money ( see Jiaozi, Guanzi, Huizi ), which circulated on a massive scale. A unify tax system and effective trade routes by road and duct mean the exploitation of a nationally market. regional specialization promoted economic efficiency and increase productiveness. Although much of the central government ‘s treasury went to the military, taxes imposed on the rising commercial base refilled the coffers and promote encouraged the monetary economy. [ 3 ] Reformers and conservatives debated the function of government in the economy. The emperor butterfly and his government placid took province for the economy, but broadly made fewer claims than in earlier dynasties. The government did, however, continue to enforce monopolies on certain manufactured items and commercialize goods to boost revenues and guarantee resources that were vital to the conglomerate ‘s security, such as tea, salt, and chemical components for gunpowder. These changes led some historians to call Song China an “ early modern ” economy centuries before Western Europe made its breakthrough. many of these gains were lost, however, in the follow yuan and Ming dynasties, which replaced the Song use of market mechanisms with top-down instruction strategies.

farming [edit ]

A “ seedling horse ” invented during the Song dynasty to pluck out seedlings, 18th c. absorb There was a massive expansion of cultivated land during the Song dynasty. The government encouraged people to reclaim bare lands and put them under cultivation. Anyone who opened up new lands and paid taxes were granted permanent possession of the new bring. Under this policy, the cultivated land in the Song dynasty is estimated to have reached a bill act of 720 million mu ( 48 million hectares ) and was not surpassed by late Ming and Qing dynasties. [ 4 ] irrigation of arable land was besides greatly fostered during this period. outstanding statesman and economist Wang Anshi issued the Law and Decree on Irrigation in 1069 that encouraged expansion of the irrigation system in China. By 1076, approximately 10,800 irrigation projects were completed, which irrigated more than 36 million mu of populace and secret domain. [ 5 ] Major irrigation projects included dredging the Yellow River at northern China and artificial silt up farming in the Lake Tai valley. As a consequence of this policy, crop production in China tripled. [ 6 ] agricultural yields were about 2 tan ( a unit of about 110 pounds or 50 kilograms ) of grain per mu during the Song dynasty, compared with 1 tan during the early Han and 1.5 tan during the former Tang. [ 7 ] The economic development of China under the Song dynasty was marked by improvements in farm tools, seeds, and fertilizers. The Song inherited the cover innovations described in the Tang dynasty text The Classic of the Plow, which documents their utilization in Jiangnan. [ 8 ] The Song improved on the Tang curved iron plow and invented a extra sword plough design specifically for reclaiming barren. The barren big dipper was not made of iron, but of stronger steel, the blade was shorter but chummy, and particularly effective in cutting through reeds and roots in wetlands in the Huai River valley. A tool designed to facilitate seedling called “ seedling horse ” was invented under the Song ; it was made of jujube wood and paulownia forest. song farms used bamboo body of water wheels to harness the run energy of rivers to raise body of water for irrigation of cultivated land .

A “ seedling horse ” invented during the Song dynasty to pluck out seedlings, 18th c. absorb There was a massive expansion of cultivated land during the Song dynasty. The government encouraged people to reclaim bare lands and put them under cultivation. Anyone who opened up new lands and paid taxes were granted permanent possession of the new bring. Under this policy, the cultivated land in the Song dynasty is estimated to have reached a bill act of 720 million mu ( 48 million hectares ) and was not surpassed by late Ming and Qing dynasties. [ 4 ] irrigation of arable land was besides greatly fostered during this period. outstanding statesman and economist Wang Anshi issued the Law and Decree on Irrigation in 1069 that encouraged expansion of the irrigation system in China. By 1076, approximately 10,800 irrigation projects were completed, which irrigated more than 36 million mu of populace and secret domain. [ 5 ] Major irrigation projects included dredging the Yellow River at northern China and artificial silt up farming in the Lake Tai valley. As a consequence of this policy, crop production in China tripled. [ 6 ] agricultural yields were about 2 tan ( a unit of about 110 pounds or 50 kilograms ) of grain per mu during the Song dynasty, compared with 1 tan during the early Han and 1.5 tan during the former Tang. [ 7 ] The economic development of China under the Song dynasty was marked by improvements in farm tools, seeds, and fertilizers. The Song inherited the cover innovations described in the Tang dynasty text The Classic of the Plow, which documents their utilization in Jiangnan. [ 8 ] The Song improved on the Tang curved iron plow and invented a extra sword plough design specifically for reclaiming barren. The barren big dipper was not made of iron, but of stronger steel, the blade was shorter but chummy, and particularly effective in cutting through reeds and roots in wetlands in the Huai River valley. A tool designed to facilitate seedling called “ seedling horse ” was invented under the Song ; it was made of jujube wood and paulownia forest. song farms used bamboo body of water wheels to harness the run energy of rivers to raise body of water for irrigation of cultivated land .

While there was already a great diversity in agrarian implements of the tread cover ( tali 踏犁 ) because of lacking ox, of lever-knife ( zhadao 鍘刀 ) and the northeastern-style plow ( tang 耥 ), the consumption of water system exponent to move millstones, grinding stones and hammers and to move water from canals and rivers to irrigation ditches by a chained-buckets mechanism ( fanche 翻車 ) became more and more usual, particularly with big land owners. Until then, water system was hoisted by a mechanism where big step-powered wheels ( tache 踏車 ) moved chain buckets with water from the river to a chuck. As an inplement to pluck out rice seedlings peasants made use of the “ seedling knight ” ( yangma 秧馬 ), planting and fertilize was the undertaking of a machine called “ dung-drill ” ( fenlou 糞耬 ). In northern China, a “ drill-tiller ” ( louchu 耬耡 ) was in use, while in the lower Yangtze area, a “ plow-weeder ” ( tangyun 耥耘 ) became widespread at the conclusion of Southern Song. For harvesting, a pushing scythe ( tuilian 推鐮 ) with two wheels was invented. [ 9 ] — Ulrich Theobald

The water wheel was about 30 chi in diameter, with ten bamboo watering tubes fastened at its perimeter. Some farmers even used three stage watering wheels to lift body of water to a acme of over 30 chi. high gear yield Champa paddy seeds, Korean yellow paddy, indian fleeceable pea, and Middle East watermelon were introduced into China during this period, greatly enhancing the variety of farm grow. Song farmers emphasized the importance of nox soil as fertilizer. They understood that using night dirt could transform barren barren into fat farmland. Chen Pu wrote in his Book of Agriculture of 1149 : “ The coarse saying that cultivated land becomes exhausted after seeding three to five years is not correctly, if frequently top up with modern dirt and cure with night dirt, then the bring becomes more fecund ”. [ 10 ]

economic crops [edit ]

louchu) from the Nong shu, Yuan dynasty A drill-tiller ( ) from the cotton was introduced from Hainan Island into central China. cotton flowers were collected, pits removed, beaten free with bamboo bows, drawn into yarns and weaved into fabric called “ jibei ”. ” [ 11 ] The cotton jibei made in Hainan has great diverseness, the fabric has capital width, frequently dyed into bright colors, stitching up two pieces make a bedspread, stitching four pieces make a curtain [ 12 ] Hemp was besides widely planted and made into linen. Independent mulberry farms flourished in the Mount Dongting area in Suzhou. The mulberry farmers did not make a populate on cultivated land, but rather they grew mulberry trees and bred silkworm to harvest silk. Sugarcane foremost appeared in China during the Warring States period. During the Song dynasty, Lake Tai valley was celebrated for the sugarcane cultivated. Song writer Wang Zhuo described in great contingent the method acting of cultivating sugarcane and how to make cane sugar flour from sugarcane in his monography “ Classic of Sugar ” in 1154, the foremost book about carbohydrate engineering in China. [ 13 ] Tea grove in the Song dynasty was three times the size that it during the Tang dynasty. According to a view in 1162, tea plantations were spread across 66 prefectures in 244 counties. [ 14 ] The Beiyuan Plantation ( North Park Plantation ) was an imperial tea plantation in Fujian prefecture. It produced more than forty varieties of tribute tea for the imperial court. lone the very peak of tender tea leaves were picked, processed and pressed into tea cakes, embossed with draco design, known as “ dragon tea cakes ”. [ 15 ] With the growth of cities, high value vegetable farms sprung up in the suburb. In southern China, on average one mu of paddy farm land supported one man, while in the north about three mu for one man, while one mu of vegetable farm supported three men. [ 16 ]

louchu) from the Nong shu, Yuan dynasty A drill-tiller ( ) from the cotton was introduced from Hainan Island into central China. cotton flowers were collected, pits removed, beaten free with bamboo bows, drawn into yarns and weaved into fabric called “ jibei ”. ” [ 11 ] The cotton jibei made in Hainan has great diverseness, the fabric has capital width, frequently dyed into bright colors, stitching up two pieces make a bedspread, stitching four pieces make a curtain [ 12 ] Hemp was besides widely planted and made into linen. Independent mulberry farms flourished in the Mount Dongting area in Suzhou. The mulberry farmers did not make a populate on cultivated land, but rather they grew mulberry trees and bred silkworm to harvest silk. Sugarcane foremost appeared in China during the Warring States period. During the Song dynasty, Lake Tai valley was celebrated for the sugarcane cultivated. Song writer Wang Zhuo described in great contingent the method acting of cultivating sugarcane and how to make cane sugar flour from sugarcane in his monography “ Classic of Sugar ” in 1154, the foremost book about carbohydrate engineering in China. [ 13 ] Tea grove in the Song dynasty was three times the size that it during the Tang dynasty. According to a view in 1162, tea plantations were spread across 66 prefectures in 244 counties. [ 14 ] The Beiyuan Plantation ( North Park Plantation ) was an imperial tea plantation in Fujian prefecture. It produced more than forty varieties of tribute tea for the imperial court. lone the very peak of tender tea leaves were picked, processed and pressed into tea cakes, embossed with draco design, known as “ dragon tea cakes ”. [ 15 ] With the growth of cities, high value vegetable farms sprung up in the suburb. In southern China, on average one mu of paddy farm land supported one man, while in the north about three mu for one man, while one mu of vegetable farm supported three men. [ 16 ]

Organization, investing, and trade [edit ]

tea in the form of a coat, called the bad dragon coat, Song dynasty

tea in the form of a coat, called the bad dragon coat, Song dynasty  Nong shu, Yuan dynasty Hydro-powered hammer from the

Nong shu, Yuan dynasty Hydro-powered hammer from the

commercialization [edit ]

Although boastfully government-run industries and big privately owned enterprises dominated the market organization of urban China during the Song period, there was a overplus of little individual businesses and entrepreneurs throughout the big suburbs and rural areas that thrived off the economic boom of the period. There was even a boastfully black commercialize in China during the Song menstruation, which was actually enhanced once the Jurchens conquered northern China and established the Jin dynasty. For exercise, around 1160 AD there was an annual black market smuggle of some 70 to 80 thousand cattle. [ 17 ] There were multitudes of successful small kiln and pottery shops owned by local families, along with anoint presses, wine-making shops, minor local paper-making businesses, etc. [ 18 ] There was besides room for belittled economic success with the “ hostel custodian, the junior-grade divine, the drug seller, the fabric trader ”, and many others. [ 19 ] rural families that sold a bombastic agrarian excess to the market not only could afford to buy more charcoal, tea, anoint, and wine, but they could besides amass enough funds to establish secondary means of product for generating more wealth. [ 20 ] Besides necessity agricultural foodstuffs, farming families could much produce wine, charcoal, newspaper, textiles, and other goods they sold through brokers. [ 20 ] Farmers in Suzhou frequently specialized in raising bombyx mori to produce silk wares, while in Fujian, Sichuan, and Guangdong farmers frequently grew sugarcane. [ 20 ] In order to ensure the prosperity of rural areas, technical applications for populace works projects and improved agrarian techniques were substantive. The huge irrigation organization of China had to be furnished with multitudes of wheelwrights mass-producing standardized waterwheels and square-pallet chain pumps that could lift body of water from lower planes to higher irrigation planes. [ 21 ] For dress, silken robes were worn by the affluent and elite while cannabis and ramie was worn by the poor ; by the late Song period cotton clothes were besides in function. [ 20 ] Shipment of all these materials and goods was aided by the tenth century invention of the duct beat lock in China ; the Song scientist and statesman Shen Kuo ( 1031–1095 ) wrote that the construction of sudanese pound lock gates at Zhenzhou ( presumably Kuozhou along the Yangtze ) during the 1020s and 1030s freed up the use of five hundred working laborers at the canal each class, amounting to the save of up to 1,250,000 strings of cash per annum. [ 22 ] He wrote that the honest-to-god method of hauling boats over limited the size of the cargo to 300 tan of rice per vessel ( roughly 17 t/17,000 kilogram ), but after the ram locks were introduced, boats carrying 400 tan ( roughly 22 t/22,000 kilogram ) could then be used. [ 22 ] Shen wrote that by his time ( c. 1080 ) government boats could carry cargo weights of up to 700 tan ( 39 t/39,000 kilogram ), while private boats could hold deoxyadenosine monophosphate much as 800 bags, each weighing 2 tan ( i.e. a sum of 88 t/88,000 kilogram ). [ 22 ]

urban employment and businesses [edit ]

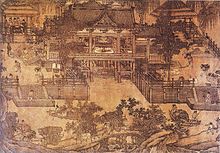

The city economy offered a new range of professions and places of oeuvre. After the fall of North China, one nostalgic writer delighted in describing each location and clientele in the former capital, Bianjing, near contemporary Kaifeng. In Dongjing Meng Hua Lu (Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital) he writes of the alleys and avenues around the East Gate of the Xiangguo Temple in Kaifeng ,

Along the Temple Eastgate Avenue … are to be found shops specializing in fabric caps with point tails, belts and waiststraps, books, caps and flowers ampere well as the vegetarian tea meal of the Ding family … South of the temple are the brothels of Manager ‘s Alley … The nuns and the brocade workers live in Embroidery Alley … On the union is little Sweetwater Alley … There are a particularly large number of southerly restaurants inside the bowling alley, equally good as a overplus of brothels. [ 23 ]

similarly, in the “ Pleasure District ” [ 24 ] along the Horse Guild Avenue, near a zoroastrian temple in Kaifeng, he writes :

In addition to the family gates and shops that line the two sides of New Fengqiu Gate Street … military encampments of the assorted brigades and column [ of the Imperial Guard ] are situated in facing pairs along approximately ten-spot li of the set about to the gate. early wards, alleys, and confined open spaces crisscross the area, numbering in the tens of thousands—none knows their real count. In every individual place, the gates are squeezed up against each other, each with its own tea wards, wineshops, stages, and food and drink. normally the modest business households of the marketplace plainly purchase [ prepared ] food and toast at food stores ; they do not cook at base. For northerly food there are the Shi Feng style dried kernel cubes … made of assorted grizzle items … for southerly food, the House of Jin at Temple Bridge … and the House of Zhou at Ninebends … are acknowledged to be the finest. The night markets close after the third watch only to reopen at the fifth. [ 25 ]

Night Revels of Han Xizai; in this scene there are two musicians and a dancer entertaining the guests of Han Xizai. A section of the twelfth hundred remake of Gu Hongzhong ‘s tenth hundred ; in this scene there are two musicians and a dancer entertaining the guests of Han Xizai. Kaifeng shopkeepers rarely had prison term to eat at home, so they chose to go out and eat at a kind of places such as restaurants, temples, and food stalls. [ 26 ] Restaurant businesses thrived on this new clientele, [ 26 ] while restaurants that catered to regional fudge targeted customers such as merchants and officials who came from regions of China where cuisine styles and flavors were drastically unlike than those normally served in the capital. [ 27 ] [ 28 ] The pleasure zone mentioned above—where stunts, games, theatrical performance stage performances, taverns and singing girl houses were located—was teeming with food stalls where business could be had about all night. [ 26 ] [ 29 ] The success of the theater industry helped the food diligence in the cities. [ 26 ] Of the fifty some theatres within the pleasure districts of Kaifeng, four of these could entertain audiences of respective thousand each, drawing huge crowd which would then give nearby businesses an enormous potential customer root. [ 30 ] Besides food, traders in eagles and hawk, precious paintings, a well as shops selling bolts of silk and fabric, jewelry of pearls, tire, rhinoceros horn, gold and silver, haircloth ornaments, combs, caps, scarves, and aromatic incense thrived in the marketplaces. [ 31 ]

Night Revels of Han Xizai; in this scene there are two musicians and a dancer entertaining the guests of Han Xizai. A section of the twelfth hundred remake of Gu Hongzhong ‘s tenth hundred ; in this scene there are two musicians and a dancer entertaining the guests of Han Xizai. Kaifeng shopkeepers rarely had prison term to eat at home, so they chose to go out and eat at a kind of places such as restaurants, temples, and food stalls. [ 26 ] Restaurant businesses thrived on this new clientele, [ 26 ] while restaurants that catered to regional fudge targeted customers such as merchants and officials who came from regions of China where cuisine styles and flavors were drastically unlike than those normally served in the capital. [ 27 ] [ 28 ] The pleasure zone mentioned above—where stunts, games, theatrical performance stage performances, taverns and singing girl houses were located—was teeming with food stalls where business could be had about all night. [ 26 ] [ 29 ] The success of the theater industry helped the food diligence in the cities. [ 26 ] Of the fifty some theatres within the pleasure districts of Kaifeng, four of these could entertain audiences of respective thousand each, drawing huge crowd which would then give nearby businesses an enormous potential customer root. [ 30 ] Besides food, traders in eagles and hawk, precious paintings, a well as shops selling bolts of silk and fabric, jewelry of pearls, tire, rhinoceros horn, gold and silver, haircloth ornaments, combs, caps, scarves, and aromatic incense thrived in the marketplaces. [ 31 ]

Government monopolies and private businesses [edit ]

The arrangement of allowing competitive industry to flourish in some regions while setting up its opposite of rigorous government-regulated and monopolize production and trade in others was not exclusive to iron manufacture. [ 32 ] In the beginning of the Song, the government supported competitive silk mills and brocade workshops in the easterly provinces and in the capital city of Kaifeng. [ 32 ] however, at the same prison term the government established rigid legal prohibition on the merchant craft of privately produced silk in Sichuan province. [ 32 ] This prohibition dealt an economic blow to Sichuan that caused a little rebellion ( which was subdued ), yet Song Sichuan was well known for its independent industries producing timber and cultivated oranges. [ 32 ] The reforms of the Chancellor Wang Anshi ( 1021–1086 ) sparked inflame argue amongst ministers of court when he nationalized the industries fabricate, process, and distributing tea, salt, and wine. [ 33 ] The state monopoly on Sichuan tea was the prime beginning of gross for the country ‘s purchase of horses in Qinghai for the Song army ‘s cavalry forces. [ 34 ] Wang ‘s restrictions on the individual industry and trade of strategic arms limitation talks were even criticized in a celebrated poem by Su Shi, and while the opposing politically charged cabal at court gained advantage and lost favor, Wang Anshi ‘s reforms were continually abandoned and reinstated. [ 33 ] Despite this political quarrel, the Song Empire ‘s independent beginning of tax income continued to come from state-managed monopolies and indirect taxes. [ 35 ] As for private entrepreneurship, bang-up profits could distillery be pursued by the merchants in the lavishness item trades and specify regional product. For exemplar, the silk producers of Raoyang County, Shenzhou Prefecture, southern Hebei state were specially known for producing satiny headwear for the Song emperor butterfly and high court officials in the capital. [ 36 ]

Foreign deal [edit ]

Sea barter to the South East Pacific, the Hindu world, the Islamic global, and the East African world brought merchants big luck. [ 37 ] Although the massive deal along the Grand Canal, the Yangtze River, its tributaries and lakes, and other canal systems trumped the commercial gains of overseas trade, [ 38 ] there were even many large seaports during the Song menstruation that bolstered the economy, such as Quanzhou, Fuzhou, Guangzhou, and Xiamen. These seaports, now connected to the backwoods via canal, lake, and river dealings, acted as a string of large grocery store centers for the sale of cash crops produced in the interior. [ 39 ] The high demand in China for extraneous lavishness goods and spices coming from the East Indies facilitated the growth of chinese nautical trade wind. [ 40 ] Along with the mining industry, the shipbuilding diligence of Fujian state increased its production exponentially as maritime deal was given more importance and as the state ‘s population began to increase dramatically. [ 17 ] A capacious duct connected Southern Song capital at Hangzhou connected its waterways to the seaport at Mingzhou ( modern Ningbo ), the center where many of the imported goods were shipped out to the rest of the area. [ 41 ] Pearls, ivory, rhinoceros horns, frankincense, agalloch eaglewood, coral, agate, hawksbill turtle turtle shell, gardenia, and rose were imported from the Arabs. Samboja and herb tea medicate came from Java, while costusroot was imported from Foloan ( Kuala Sungai Berang ), cotton fabric and cotton narration from Mait, and ginseng, silver medal, copper, and erratic from Korea. [ 42 ] Despite the initiation of fuel stations and a large fire fighting push, fires continued to threaten the city of Hangzhou and the respective businesses within it. [ 43 ] In safeguarding store supplies and providing lease space for merchants and shopkeepers to keep their excess goods condom from city fires, the full-bodied families of Hangzhou, palace eunuch, and empresses had big warehouses built near the northeasterly walls ; these warehouses were surrounded by channels of urine on all sides and were heavily guarded by hire night watchmen. [ 44 ] Shipbuilders generated means of employment for many skilled craftsmen, while sailors for ship crews found many opportunities of employment as more families had enough capital to purchase boats and invest in commercial trade afield. [ 45 ] Foreigners and merchants from abroad affected the economy from within China deoxyadenosine monophosphate well. For exercise, many Muslims went to Song China not entirely to trade, but dominated the spell and export industry and in some cases became officials of economic regulations. [ 46 ] [ 47 ] For chinese nautical merchants, however, there was hazard involved in such long oversea ventures to foreign trade posts and seaports as far away as Egypt. [ 48 ] In order to reduce the risk of losing money alternatively of gaining it on nautical craft missions afield, investors prudently spread their investing among several ships, each of which had a number of investors .

A 10th or eleventh hundred Longquan stoneware vase from Zhejiang province, Song dynasty. One perceiver thought his countrymen ‘s investments would lead to an spring of copper cash. He wrote, “ People along the seashore are on intimate terms with the merchants who engage in abroad trade, either because they are fellow-countrymen or personal acquaintances … [ They give the merchants ] money to take with them on their ships for leverage and return transportation of alien goods. They invest from ten to a hundred strings of cash, and regularly make profits of several hundred percentage. ” [ 49 ]

A 10th or eleventh hundred Longquan stoneware vase from Zhejiang province, Song dynasty. One perceiver thought his countrymen ‘s investments would lead to an spring of copper cash. He wrote, “ People along the seashore are on intimate terms with the merchants who engage in abroad trade, either because they are fellow-countrymen or personal acquaintances … [ They give the merchants ] money to take with them on their ships for leverage and return transportation of alien goods. They invest from ten to a hundred strings of cash, and regularly make profits of several hundred percentage. ” [ 49 ]

Zhu Yu ‘s Pingzhou Ketan ( 萍洲可談 ; Pingzhou Table Talks ) ( 1119 ) described the organization, nautical practices, and politics standards of seagoing vessels, their merchants, and sailing crews :

According to government regulations concerning seagoing ships, the larger ones can carry respective hundred men, and the smaller ones may have more than a hundred men on control panel. One of the most significant merchants is chosen to be Leader ( Gang Shou ), another is deputy Leader ( Fu Gang Shou ), and a third is Business Manager ( Za Shi ). The overseer of Merchant Shipping gives them an unofficially sealed red certificate permitting them to use the light bamboo for punishing their party when necessity. Should anyone die at sea, his property becomes forfeit to the government … The embark ‘s pilots are acquainted with the configuration of the coasts ; at night they steer by the stars, and in the day-time by the sun. In night weather they look at the south-pointing needle ( i.e. the magnetic circumnavigate ). They besides use a line a hundred feet long with a hook at the end which they let down to take samples of mire from the sea-bottom ; by its ( appearance and ) smell they can determine their whereabouts. [ 50 ]

Read more: Australia Maritime Strategy

According to a resident of Hangzhou writing in 1274, the merchant ships came in a kind of sizes. The large ones were of 5,000 liao and could fit up to 600 passengers. The in-between size ones were between 1,000 and 2,000 liao and could carry up to 300 passengers. Smaller ships were known as “ wind-piercing ” and carried up to a hundred passengers. extraneous travelers to China frequently made remarks on the economic intensity of the country. The late Muslim Moroccan Berber traveler Ibn Battuta ( 1304–1377 ) wrote about many of his travel experiences in places across the eurasian universe, including China at the farthest eastern extremity. After describing lavish chinese ships holding palatial cabins and saloons, along with the life of chinese embark crews and captains, Batutta wrote : “ Among the inhabitants of China there are those who own numerous ships, on which they send their agents to foreign places. For nowhere in the earth are there to be found people richer than the chinese ”. [ 52 ]

Salaries and income [edit ]

affluent landholders were still typically those who were able to educate their sons to the highest degree. Hence, small groups of outstanding families in any given local county would gain national spotlight for having sons travel far off to be educated and appointed as ministers of the express, but downward sociable mobility was always an issue with the matter of divided inheritance. Suggesting ways to increase a class ‘s property, Yuan Cai ( 1140–1190 ) wrote in the late twelfth hundred that those who obtained office with decent salaries should not convert it to gold and silver but watch their values grow with investing :

For exemplify, if he had 100,000 strings deserving of gold and silver and used this money to buy generative place, in a class he would gain 10,000 strings ; after ten years or so, he would have regained the 100,000 strings and what would be divided among the family would be matter to. If it were invested in a instrument broking business, in three years the interest would equal the das kapital. He would hush have the 100,000 strings, and the rest, being interest, could be divided. furthermore, it could be doubled again in another three years, ad infinitum. [ 53 ]

Shen Kuo ( 1031–1095 ), a minister of finance, was of the lapp public opinion ; in his understand of the speed of circulation, he stated in 1077 :

The utility of money derives from circulation and loan-making. A village of ten-spot households may have 100,000 coins. If the cash is stored in the family of one individual, evening after a century, the sum remains 100,000. If the coins are circulated through business transactions so that every individual of the ten households can enjoy the utility of the 100,000 coins, then the utility will amount to that of 1,000,000 cash. If circulation continues without break, the utility of the cash will be beyond count. [ 54 ]

considerable eruditeness has been concentrated on researching the horizontal surface of support standards during the Song dynasty. A holocene sketch by economic historian Cheng Minsheng estimated the average income for lower-class laborers during the Song dynasty as 100 wen a sidereal day, about 5 times the calculate subsistence level of 20 wen a day and a very high level for preindustrial economies. Per head consumption of grain and silk respectively was estimated by Cheng to be about 8 jin ( about 400 g each ) a day and 2 bolts a year, respectively. [ 55 ]

handicraft diligence [edit ]

Nong Shu by A blast furnace smelting cast iron, with bellows operated by waterwheel and mechanical device, from theby Wang Zhen, 1313 ad

Nong Shu by A blast furnace smelting cast iron, with bellows operated by waterwheel and mechanical device, from theby Wang Zhen, 1313 ad

Steel and iron industries [edit ]

Accompanying the widespread printing of newspaper money was the beginnings of what one might term an early chinese industrial rotation. For example, the historian Robert Hartwell [ 56 ] has estimated that per caput iron output rose sixfold between 806 and 1078, such that, by 1078 China was producing 127000000 kilogram ( 125,000 metric ton ) in weight of iron per year. [ 57 ] however, historian Donald Wagner questions Hartwell ‘s method acting used to estimate these figures ( i.e. by using Song tax and quota receipts ), and believes the total receipts of cast-iron represents only a roughly approximation of total government consumption of iron. [ 58 ] even taking into account Wagner ‘s reservations, the lowest estimates still put annual cast-iron production levels at respective times higher than the Tang dynasty .

During the era of the iron monopoly, smaller bloomery furnaces – the alone iron smelting technology available in Europe before the twelfth hundred – seem to have disappeared wholly. even after the Eastern Han government rescinded the iron monopoly in 88 CE cast-iron fabricate remained confined to large-scale bang furnaces and foundries. The blast furnace engineering and the economies of scale achieved by the country ironworks in the Han obviously rendered the bloomery technology economically disused. When minor ironworks reappeared in China during the Song dynasty they were operated using little blast furnaces rather than bloomery techniques. — Richard von Glahn

In the smelting serve of using huge bellows driven by waterwheels, massive amounts of charcoal were used in the production process, leading to a wide range of deforestation in northerly China. [ 57 ] however, by the end of the eleventh hundred the Chinese discovered that using bituminous coke could replace the role of charcoal, therefore many acres of afforest kingdom in northern China were spared from the sword and iron industry with this switch of resources. [ 38 ] [ 57 ] Iron and steel of this period were used to mass-produce ploughs, hammers, needles, pins, nails for ships, musical cymbals, chains for abeyance bridges, Buddhist statues, and other routine items for an autochthonal aggregate market. [ 61 ] Iron was besides a necessity manufacture part for the production processes of salt and copper. [ 61 ] many newly constructed canals linked the major iron and steel production centers to the capital city ‘s independent marketplace. [ 18 ] This was besides extended to trade with the outside populace, which greatly expanded with the high gear floor of chinese maritime action overseas during the Southern Song menstruation. Through many written petitions to the central politics by regional administrators of the Song Empire, historic scholars can piece evidence together to appropriate the size and scope of the chinese iron industry during the Song era. The celebrated magistrate Bao Qingtian ( 999–1062 ) wrote of the iron industry at Hancheng, Tongzhou Prefecture, along the Yellow River in what is nowadays easterly Shaanxi province, with iron smelting households that were overseen by government regulators. [ 62 ] He wrote that 700 such households were acting as iron smelters, with 200 having the most adequate amount of government back, such as charcoal supplies and skilled craftsmen ( the cast-iron households hired local unskilled labor themselves ). [ 62 ] Bao ‘s complaint to the throne was that government laws against private smelt in Shaanxi hindered profits of the diligence, so the government last heeded his supplication and lifted the prohibition on secret smelt for Shaanxi in 1055. [ 62 ] [ 63 ] The resultant role of this was an increase in profit ( with lower prices for iron ) angstrom well as production ; 100,000 jin ( 60 tonnes ) of cast-iron was produced per annum in Shaanxi in the 1040s AD, increasing to 600,000 jin ( 360 tonnes ) produced per annum by the 1110s, furbished by the revival of the Shaanxi mine industry in 1112. [ 64 ] Although the cast-iron smelters of Shaanxi were managed and supplied by the government, there were many mugwump smelters operated and owned by rich people families. [ 65 ] While acting as governor of Xuzhou in 1078, the celebrated Song poet and statesman Su Shi ( 1037–1101 ) wrote that in the Liguo Industrial Prefecture under his administer region, there were 36 iron smelters run by different local families, each employing a function impel of several hundred people to mine ore, produce their own charcoal, and smelt iron. [ 65 ]

Gunpowder production [edit ]

Innovations in commerce [edit ]

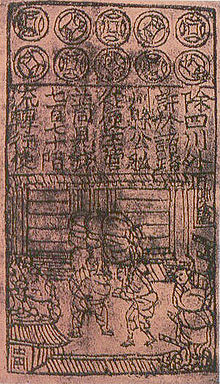

Jiaozi, the world’s first paper-printed currency, an innovation of the Song dynasty.

Jiaozi, the world’s first paper-printed currency, an innovation of the Song dynasty.

Copper resources and receipts of deposit [edit ]

The ancestor of the growth of the bill goes binding to the earlier Tang dynasty ( 618–907 ), when the politics outlawed the function of bolts of silk as currency, which increased the use of copper neologism as money. [ 72 ] By the year 1085 the output of copper currency was driven to a rate of 6 billion coins a year up from 5.86 billion in 1080 ( compared to precisely 327 million coins minted annually in the Tang ‘s comfortable Tianbao time period of 742–755, and merely 220 million coins minted per annum from 118 BC to 5 AD during the Han dynasty ). [ 72 ] [ 73 ] The expansion of the economy was unprecedented in China : the output of coinage currentness in the earlier year of 997 AD, which was alone 800 million coins a year. [ 74 ] In 1120 alone, the song government collected 18,000,000 ounces ( 510,000 kilogram ) of eloquent in taxes. [ 45 ] With many 9th hundred Tang era merchants avoiding the weight and majority of sol many copper coins in each transaction, this led them to using trading receipts from deposit shops where goods or money were left previously. [ 74 ] Merchants would deposit bull currency into the stores of affluent families and big wholesalers, whereupon they would receive receipts that could be cashed in a number of nearby towns by accredit persons. [ 75 ] Since the tenth century, the early song government began issuing their own receipts of deposition, so far this was restricted chiefly to their monopolize salt industry and deal. [ 75 ] China ‘s first official regional paper-printed money can be traced back to the year 1024, in szechwan province. [ 76 ] Although the output signal of copper currency had expanded vastly by 1085, some fifty copper mines were shut down between the years 1078 and 1085. [ 77 ] Although there were on average more copper mines found in Northern Song China than in the previous Tang dynasty, this case was reversed during the Southern Song with a sharply refuse and depletion of mined copper deposits by 1165. [ 78 ] flush though copper cash was abundant in the late eleventh century, Chancellor Wang Anshi ‘s tax substitution for corvée british labour party and government takeover of agrarian finance loans meant that people now had to find extra cash, driving up the price of copper money which would become barely. [ 79 ] To make matters worse, bombastic amounts of government-issued copper currency exited the area via external trade, while the Liao dynasty and western Xia actively pursued the exchange of their iron-minted coins for Song copper coins. [ 80 ] As evidenced by an 1103 decree, the song government became cautious about its outflow of iron currentness into the Liao Empire when it ordered that the cast-iron was to be alloyed with can in the smelt procedure, thus depriving the Liao of a prospect to melt down the currency to make cast-iron weapons. [ 81 ] The politics attempted to prohibit the use of copper currency in margin regions and in seaports, but the Song-issued bull coin became common in the Liao, Western Xia, Japanese, and Southeast asian economies. [ 80 ] The song politics would turn to other types of material for its currency in order to ease the demand on the government batch, including the issue of iron neologism and wallpaper banknotes. [ 72 ] [ 82 ] In the year 976, the percentage of issue currency using copper neologism was 65 % ; after 1135, this had dropped importantly to 54 %, a government undertake to debase the copper currentness. [ 82 ]

The world ‘s foremost paper money [edit ]

The central government soon observed the economic advantages of printing composition money, issuing a monopoly right of respective of the deposit shops to the issue of these certificates of deposition. [ 72 ] By the early twelfth century, the amount of banknotes issued in a single class amounted to an annual rate of 26 million strings of cash coins. [ 75 ] By the 1120s the central government formally stepped in and produced their own state-issued paper money ( using woodblock printing ). [ 72 ] even before this point, the birdcall government was amassing big amounts of paper tribute. It was recorded that each year before 1101 AD, the prefecture of Xinan ( modern Xi-xian, Anhui ) entirely would send 1,500,000 sheets of paper in seven different varieties to the capital at Kaifeng. [ 83 ] In that year of 1101, the Emperor Huizong of Song decided to lessen the come of newspaper taken in the tribute quota, because it was causing damaging effects and creating intemperate burdens on the people of the region. [ 84 ] however, the government hush needed masses of composition product for the exchange certificates and the state of matter ‘s new issue of paper money. For the printing of paper money alone, the Song court established respective government-run factories in the cities of Huizhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Anqi. [ 84 ] The size of the work force employed in these newspaper money factories were quite large, as it was recorded in 1175 AD that the factory at Hangzhou alone employed more than a thousand workers a day. [ 84 ] however, the government issues of composition money were not however nationally standards of currentness at that orient ; issues of banknotes were limited to regional zones of the conglomerate, and were valid for use only in a delegate and temp limit of 3-year ‘s fourth dimension. [ 75 ] [ 85 ] The geographic limitation changed between the years 1265 and 1274, when the late Southern Song government last produced a nationally standard currency of wallpaper money, once its far-flung circulation was backed by gold or flatware. [ 75 ] The range of varying values for these banknotes was possibly from one string of cash to one hundred at the most. [ 75 ] In later dynasties, the use and enforcement of newspaper currency was a method undertaken by the government as a response to the forge of copper coins. [ 86 ] The subsequent yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties would issue their own composition money as well. even the Southern Song ‘s contemporary of the Jin dynasty to the north catch on to this swerve and issued their own paper money. [ 75 ] At the archaeological excavation at Jehol there was a print plate found that dated to the year 1214, which produced notes that measured 10 curium by 19 cm in size and were worth a hundred strings of 80 cash coins. [ 75 ] This Jurchen -Jin issued wallpaper money bore a serial number, the number of the series, and a warn label that counterfeiters would be decapitated, and the denouncer rewarded with three hundred strings of cash. [ 87 ]

joint store companies [edit ]

The merchant class became more sophisticate, well-respected and organized than in earlier periods. Their wealth much rivaled that of the scholar-officials who administered the affairs of politics. They innovated in respective areas. They created partnerships and joint stock companies that separated owners ( shareholders ) from managers. Merchants were in the larger cities organized guilds that dealt in particular products and set their prices to wholesalers and workshop owners. The club heads were the representatives to the government when it requisitioned goods or assess taxes. [ 88 ] The preceding Tang dynasty saw the development of heben, the earliest form of joint store company with an active partner and passive investors. By the Song dynasty this had expanded into the douniu, a pool of shareholders with management in the hands of jingshang, merchants who operated their businesses using investors ‘ funds. A class of merchants specialising as jingshang formed. Investor compensation was based on profit-sharing, reducing the risk of person merchants and burdens of matter to payment. [ 89 ] Qin Jiushao ( c.1202–61 ), a mathematician and scholar, wrote an exercise that reflected the essential nature of these companies. He proposed that a partnership of four parties invested 424,000 strings of cash in a Southeast asian trade venture. Each invested cute metals, possibly eloquent, gold or commodities like salt, newspaper, and monk certificates ( which involved a tax exemption ). There was significant deviation in the value of their person investments, possibly equally much as eight times. Who was allowed to become an investor may have been influenced by social status and family connections, but each received a share of the profits in proportion to their original investment .

See besides [edit ]

Notes [edit ]

References [edit ]

- Benn, Charles (2002). China’s Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517665-0.

- Guo, Junning (2010). The need to put Song history in the proper perspective. China Social Science Report. Archive index at the Wayback Machine

- Bol, Peter K. “Whither the Emperor? Emperor Huizong, the New Policies, and the Tang-Song Transition”, Journal of Song and Yuan Studies, Vol. 31 (2001), pp. 103–34.

- Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ch’en, Jerome. “Sung Bronzes—An Economic Analysis”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (Volume 28, Number 3, 1965): 613–626.

- Cheng, Mingsheng (2009), Research on Song consumer prices, Beijing: People’s publishers.

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43519-6 (hardback); ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Elvin, Mark (1973). The Pattern of the Chinese Past. Stanford University Press.

- Embree, Ainslie Thomas (1997). Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. Armonk: ME Sharpe, Inc.

- Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). China: A New History; Second Enlarged Edition (2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1

- Friedman, Edward, Paul G. Pickowicz, Mark Selden. (1991). Chinese Village, Socialist State. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05428-9.

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0

- Glahn, Richard (2016), The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century

- Goldstone, Jack A. (2002). “Efflorescences and Economic Growth in World History: Rethinking the “Rise of the West” and the Industrial Revolution”, Journal of World History 13(2), 323–89.

- Hartwell, Robert M. (1962). “A Revolution in the Iron and Coal Industries During the Northern Sung, 960–1126”. Journal of Asian Studies, 21(2), 153–62.

- Hartwell, Robert M. (1966). “Markets, Technology and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry”. Journal of Economic History 26, 29–58.

- Ji Xianlin (1997) History of Cane Sugar in China, ISBN 7-80127-284-6/K

- Jones, Eric L. (2000). Growth Recurring: Economic change in world history. University of Michigan Press (with second edition introduction).

- Kelly, Morgan (1997). “The Dynamics of Smithian Growth”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(3), 939–64.

- Liu, William Guangling (2015), The Chinese Market Economy 1000-1500, Albany: SUNY Press, ISBN 9781438455679

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012), China as a Sea Power 1127-1368

- McDermott, Joseph P.; Shiba, Yoshinobu (2015). “Economic change in China, 960-1279”. In Chaffee, John; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 5.2.

- Maddison, Angus (2007). Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, second edition, revised and updated, 960 – 2030. Development Centre of the OECD.

- Mino, Yutaka and Katherine R. Tsiang (1986). Ice and Green Clouds: Traditions of Chinese Celadon. Indiana University Press.

- Mokyr, Joel (1990). The Lever of Riches: Technological creativity and economic progress. Oxford University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1969). The Grand Titration: Science and society in East and West. University of Toronto Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics.. Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press.

- Parente, Stephen L. and Edward C. Prescott (2000). Barriers to Riches. MIT Press.

- Pomeranz, Kenneth (2000). The Great Divergence: China, Europe and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton University Press.

- Qi Xia (1999), 漆侠, 中国经济通史. 宋代经济卷 /Zhongguo jing ji tong shi. Song dai jing ji juan [Economy of the Song Dynasty] vol I, II ISBN 7-80127-462-8/

- Rossabi, Morris (1988). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05913-1.

- Sadao, Nishijima. (1986). “The Economic and Social History of Former Han”, in Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 545–607. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24327-0.

- Shen, Fuwei (1996). Cultural flow between China and the outside world. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-00431-X.

- Shiba, Yoshinobu (1970a) “Commercialization of Farm Products in the Sung Period” Acta Asiatica 19, pp. 77–96.

- Shiba, Yoshinobu (1970b) Commerce and Society in Sung China, translated by Mark Elvin. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan.

- Sivin, Nathan (1982) “Why the Scientific Revolution Did Not Take Place in China – or Didn’t It?”, Chinese Science, vol. 15, 45–66.

- Smith, Paul J. (1993) “State Power and Economic Activism during the New Policies, 1068–1085′ The Tea and Horse Trade and the ‘Green Sprouts’ Loan Policy”, in Ordering the World: Approaches to State and Society in Sung Dynasty China, ed. Robert P. Hymes, 76–128. Berkeley: Berkeley University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07691-4.

- Twitchett, Denis (2015), The Cambridge History of China Volume 5-2, Cambridge University Press

- Vries, Jan de (2001) “Economic Growth before and after the Industrial Revolution: a modest proposal.” In Early Modern Capitalism: Economic and social change in Europe, edited by Maarten Prak, 177–94. Routledge.

- Wagner, Donald B. “The Administration of the Iron Industry in Eleventh-Century China”, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (Volume 44 2001): 175–197.

- Walton, Linda (1999). Academies and Society in Southern Sung China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Wrigley, Edward A. (1999). Continuity, chance and change: The character of the industrial revolution in England. Cambridge University Press.

- West, Stephen H. “Playing With Food: Performance, Food, and The Aesthetics of Artificiality in The Sung and Yuan”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies (Volume 57, Number 1, 1997): 67–106.

- Yang, Lien-sheng. “Economic Justification for Spending-An Uncommon Idea in Traditional China”, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies (Volume 20, Number 1/2, 1957): 36–52.

- Yunming, Zhang (1986). Isis: The History of Science Society: Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Zhou Qufei, (1178) Ling Wai Dai Da (Report from Lingnan), Zhong Hua Book Co ISBN 7-101-01665-0/K