American Great Lakes bottom 1958–1975

SS Edmund Fitzgerald in 1971 SS Edmund Fitzgerald in 1971 |

|

| History | |

|---|---|

Reading: SS Edmund Fitzgerald – Wikipedia |

|

| Name | SS Edmund Fitzgerald |

| Namesake | Edmund Fitzgerald, president of Northwestern Mutual |

| Owner | Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company |

| Operator | Columbia Transportation Division, Oglebay Norton Company of Cleveland, Ohio |

| Port of registry | Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Ordered | February 1, 1957 |

| Yard number | 301 |

| Laid down | August 7, 1957 |

| Launched | June 7, 1958 |

| Maiden voyage | September 24, 1958 |

| In service | June 8, 1958 |

| Out of service | November 10, 1975 |

| Identification | Registry number US 277437 |

| Nickname(s) | Fitz, Mighty Fitz, Big Fitz, Pride of the American Side, Toledo Express, Titanic of the Great Lakes |

| Fate | Lost with all hands (29 crew) in a storm, November 10, 1975 |

| Status | Wreck |

| Notes | Location: Coordinates: |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Lake freighter |

| Tonnage |

|

| Length |

|

| Beam | 75 ft (23 m) |

| Draft | 25 ft (7.6 m) typical |

| Depth | 39 ft (12 m) (moulded) |

| Depth of hold | 33 ft 4 in (10.16 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | Single fixed pitch 19.5 ft (5.9 m) propeller |

| Speed | 14 kn (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Capacity | 25,400 tons of cargo |

| Crew | 29 |

SS Edmund Fitzgerald was an american Great Lakes bottom that sank in Lake Superior during a storm on November 10, 1975, with the passing of the integral crew of 29 men. When launched on June 7, 1958, she was the largest ship on North America ‘s Great Lakes, and she remains the largest to have sink there. She was located in deep body of water on November 14, 1975, by a U.S. Navy aircraft detecting magnetic anomalies, and found soon afterwards to be in two big pieces. For 17 years, Edmund Fitzgerald carried taconite iron ore from mines near Duluth, Minnesota, to iron works in Detroit, Toledo, and early Great Lakes ports. As a workhorse, she set seasonal worker haul records six times, often breaking her own record. Captain Peter Pulcer was known for piping music day or night over the embark ‘s intercommunication system while passing through the St. Clair and Detroit rivers ( between lakes Huron and Erie ), and entertaining spectators at the Soo Locks ( between Lakes Superior and Huron ) with a hunt comment about the ship. Her size, record-breaking performance, and “ DJ master ” endeared Edmund Fitzgerald to boat watchers. Carrying a full cargo of ore pellets with Captain Ernest M. McSorley in command, she embarked on her doomed voyage from Superior, Wisconsin, near Duluth, on the afternoon of November 9, 1975. En road to a sword factory near Detroit, Edmund Fitzgerald joined a second taconite bottom, SS Arthur M. Anderson. By the future day, the two ships were caught in a severe storm on Lake Superior, with about hurricane-force winds and waves up to 35 feet ( 11 molarity ) high. concisely after 7:10 post meridiem, Edmund Fitzgerald abruptly sank in Canadian ( Ontario ) waters 530 feet ( 88 fathoms ; 160 molarity ) deep, about 17 miles ( 15 nautical miles ; 27 kilometers ) from whitefish Bay near the twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario —a distance Edmund Fitzgerald could have covered in equitable over an hour at her top accelerate. Edmund Fitzgerald previously reported being in significant difficulty to Arthur M. Anderson : “ I have a bad list, lost both radars. And am taking heavy seas over the deck. One of the worst seas I ‘ve ever been in. ” however, no distress signals were sent before she sank ; Captain McSorley ‘s last ( 7:10 post meridiem ) message to Arthur M. Anderson was, “ We are holding our own. ” Her gang of 29 perished, and no bodies were recovered. The demand cause of the sink remains unknown, though many books, studies, and expeditions have examined it. Edmund Fitzgerald may have been swamped, suffered structural failure or topside damage, experienced shallow, or suffered from a combination of these. The catastrophe is one of the best known in the history of Great Lakes transportation. Gordon Lightfoot made it the subject of his 1976 hit sung “ The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald “ after reading an article, “ The Cruelest Month ”, in the November 24, 1975, issue of Newsweek. The sink led to changes in Great Lakes ship regulations and practices that included mandate survival suits, depth finders, positioning systems, increased freeboard, and more frequent inspection of vessels .

history [edit ]

Edmund Fitzgerald, upbound and in SSupbound and in ballast

Edmund Fitzgerald, upbound and in SSupbound and in ballast

design and structure [edit ]

Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, invested in the iron and minerals industries on a large-scale basis, including the construction of Edmund Fitzgerald, which represented the inaugural such investment by any american biography indemnity company. In 1957, they contracted Great Lakes Engineering Works ( GLEW ), of River Rouge, Michigan, to design and construct the embark “ within a foot of the maximal duration allowed for passage through the soon-to-be completed Saint Lawrence Seaway. ” The ship ‘s value at that clock was $ 7 million ( equivalent to $ 49.7 million in 2019 [ 10 ] ). Edmund Fitzgerald was the first laker built to the maximal St. Lawrence Seaway size, which was 730 feet ( 222.5 molarity ) long, 75 feet ( 22.9 meter ) across-the-board, and with a 25 foot ( 7.6 thousand ) draft. The cast depth ( roughly speaking, the erect altitude of the hull ) was 39 foot ( 12 meter ). The hold depth ( the inside height of the cargo carry ) was 33 foot 4 in ( 10.16 molarity ). GLEW laid the first keel plate on August 7 the like year. With a deadweight capacitance of 26,000 long tons ( 29,120 short tons ; 26,417 thymine ), and a 729-foot ( 222 m ) hull, Edmund Fitzgerald was the longest transport on the Great Lakes, earning her the title Queen of the Lakes until September 17, 1959, when the 730-foot ( 222.5 thousand ) SS Murray Bay was launched. Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s three central cargo holds were loaded through 21 watertight cargo hatches, each 11 by 48 feet ( 3.4 by 14.6 m ) of 5⁄16-inch-thick ( 7.9 millimeter ) steel. originally coal-fired, her boilers were converted to burn anoint during the 1971–72 winter lay-up. In 1969, the ship ‘s maneuverability was improved by the initiation of a diesel-powered bow thruster. By ore bottom standards, the interior of Edmund Fitzgerald was deluxe. Her J.L. Hudson Company -designed furnishings included deep pile carpet, tiled bathrooms, drapes over the portholes, and leather pivot chairs in the guest loiter. There were two guest staterooms for passengers. Air conditioning extended to the gang quarters, which featured more amenities than common. A big galley and in full stocked pantry supplied meals for two boom rooms. Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s pilothouse was outfitted with “ state-of-the-art nautical equipment and a beautiful map room. ”

name and plunge [edit ]

northwestern Mutual named the ship after its president and chair of the dining table, Edmund Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald ‘s own grandfather had himself been a lake captain, and his forefather owned the Milwaukee Drydock Company, which built and repaired ships. More than 15,000 people attended Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s christening and launch ceremony on June 7, 1958. The consequence was plagued by misfortunes. When Elizabeth Fitzgerald, wife of Edmund Fitzgerald, tried to christen the ship by smashing a champagne bottle over the crouch, it took her three attempts to break it. A check of 36 minutes followed while the shipyard gang struggled to release the stagger blocks. Upon sideway launch, the ship created a bombastic wave that “ dip ” the spectators and then crashed into a pier before righting herself. One man watching the launch had a heart attack and later died. early witnesses subsequently said they swore the ship was “ trying to climb right out of the urine ”. On September 22, 1958, Edmund Fitzgerald completed nine days of ocean trials .

career [edit ]

Edmund Fitzgerald under way SSunder way Northwestern Mutual ‘s normal drill was to purchase ships for operation by other companies. In Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s case, they signed a 25-year compress with Oglebay Norton Corporation to operate the vessel. Oglebay Norton immediately designated Edmund Fitzgerald the flagship of its Columbia Transportation flit. Edmund Fitzgerald was a record-setting workhorse, much beating her own milestones. The vessel ‘s record warhead for a one tripper was 27,402 long tons ( 30,690 inadequate tons ; 27,842 metric ton ) in 1969. For 17 years, Edmund Fitzgerald carried taconite from Minnesota ‘s Iron Range mines near Duluth, Minnesota, to iron works in Detroit, Toledo, and other ports. She set seasonal worker haul records six different times. Her nicknames included “ Fitz ”, “ pride of the american Side ”, “ Mighty Fitz ”, “ Toledo Express ”, “ adult Fitz ”, and the “ Titanic of the Great Lakes ”. Loading Edmund Fitzgerald with taconite pellets took about four and a half hours, while unloading took about 14 hours. A attack trip between Superior, Wisconsin, and Detroit, Michigan, normally took her five days and she averaged 47 similar trips per season. The vessel ‘s common route was between Superior, Wisconsin, and Toledo, Ohio, although her port of finish could vary. By November 1975, Edmund Fitzgerald had logged an estimated 748 round trips on the Great Lakes and covered more than a million miles, “ a distance roughly equivalent to 44 trips around the global. ” up until a few weeks before her loss, passengers had traveled on board as company guests. Frederick Stonehouse wrote :

Edmund Fitzgerald under way SSunder way Northwestern Mutual ‘s normal drill was to purchase ships for operation by other companies. In Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s case, they signed a 25-year compress with Oglebay Norton Corporation to operate the vessel. Oglebay Norton immediately designated Edmund Fitzgerald the flagship of its Columbia Transportation flit. Edmund Fitzgerald was a record-setting workhorse, much beating her own milestones. The vessel ‘s record warhead for a one tripper was 27,402 long tons ( 30,690 inadequate tons ; 27,842 metric ton ) in 1969. For 17 years, Edmund Fitzgerald carried taconite from Minnesota ‘s Iron Range mines near Duluth, Minnesota, to iron works in Detroit, Toledo, and other ports. She set seasonal worker haul records six different times. Her nicknames included “ Fitz ”, “ pride of the american Side ”, “ Mighty Fitz ”, “ Toledo Express ”, “ adult Fitz ”, and the “ Titanic of the Great Lakes ”. Loading Edmund Fitzgerald with taconite pellets took about four and a half hours, while unloading took about 14 hours. A attack trip between Superior, Wisconsin, and Detroit, Michigan, normally took her five days and she averaged 47 similar trips per season. The vessel ‘s common route was between Superior, Wisconsin, and Toledo, Ohio, although her port of finish could vary. By November 1975, Edmund Fitzgerald had logged an estimated 748 round trips on the Great Lakes and covered more than a million miles, “ a distance roughly equivalent to 44 trips around the global. ” up until a few weeks before her loss, passengers had traveled on board as company guests. Frederick Stonehouse wrote :

Stewards treated the guests to the stallion VIP routine. The cuisine was reportedly excellent and snacks were constantly available in the lounge. A small but well-stocked kitchenette provided the drinks. once each slip, the captain held a candlelight dinner for the guests, dispatch with mess-jacketed stewards and special “ clamdigger ” punch .

Because of her size, appearance, string of records, and “ DJ captain, ” Edmund Fitzgerald became a front-runner of gravy boat watchers throughout her career. Although Captain Peter Pulcer was in instruction of Edmund Fitzgerald on trips when cargo records were set, “ he is good remembered … for piping music day or nox over the ship ‘s intercommunication system system ” while passing through the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers. While navigating the Soo Locks he would much come out of the pilothouse and use a bullhorn to entertain tourists with a comment on details about Edmund Fitzgerald. In 1969, Edmund Fitzgerald received a safety award for eight years of operation without a time-off actor wound. The vessel ran aground in 1969, and she collided with SS Hochelaga in 1970. late that same year, she struck the wall of a lock, an accident repeated in 1973 and 1974. During 1974, she lost her original bow anchor in the Detroit River. none of these mishaps, however, were considered unplayful or unusual. Freshwater ships are built to last more than half a century, and Edmund Fitzgerald would even have had a long career ahead of her when she sank .

final voyage and shipwreck [edit ]

Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur M. Anderson The National Transportation Safety Board function of probable course ofand

Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur M. Anderson The National Transportation Safety Board function of probable course ofand Map showing the location of the wreck Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin, at 2:15 post meridiem on the good afternoon of November 9, 1975, under the command of Captain Ernest M. McSorley. She was en path to the steel mill on Zug Island, near Detroit, Michigan, with a cargo of 26,116 long tons ( 29,250 short-circuit tons ; 26,535 thymine ) of taconite ore pellets and soon reached her full travel rapidly of 16.3 miles per hour ( 14.2 kn ; 26.2 kilometers per hour ). Around 5 post meridiem, Edmund Fitzgerald joined a moment bottom under the command of Captain Jesse B. “ Bernie ” Cooper, Arthur M. Anderson, destined for Gary, Indiana, out of Two Harbors, Minnesota. The upwind prognosis was not unusual for November and the National Weather Service ( NWS ) predicted that a storm would pass just south of Lake Superior by 7 ante meridiem on November 10. SS Wilfred Sykes loaded opposite Edmund Fitzgerald at the Burlington Northern Dock # 1 and departed at 4:15 post meridiem, about two hours after Edmund Fitzgerald. In contrast to the NWS prognosis, Captain Dudley J. Paquette of Wilfred Sykes predicted that a major ramp would directly cross Lake Superior. From the beginning, he chose a path that took advantage of the protection offered by the lake ‘s north shore to avoid the worst effects of the storm. The crew of Wilfred Sykes followed the radio conversations between Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur M. Anderson during the foremost separate of their trip and overheard their captains deciding to take the even Lake Carriers ‘ Association downbound route. The NWS altered its forecast at 7:00 post meridiem, issuing gale warnings for the whole of Lake Superior. Arthur M. Anderson and Edmund Fitzgerald altered naturally northbound seeking protection along the Ontario shore where they encountered a winter storm at 1:00 ante meridiem on November 10. Edmund Fitzgerald reported winds of 52 knots ( 96 kilometers per hour ; 60 miles per hour ) and waves 10 feet ( 3.0 meter ) high. Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes reported that after 1 ante meridiem, he overheard McSorley say that he had reduced the ship ‘s speed because of the rocky conditions. Paquette said he was stunned to later hear McSorley, who was not known for turning aside or slowing down, state that “ we ‘re going to try for some lee from Isle Royale. You ‘re walking off from us anyhow … I ca n’t stay with you. ” At 2:00 ante meridiem on November 10, the NWS upgraded its warnings from gale to storm, forecasting winds of 35–50 knots ( 65–93 kilometers per hour ; 40–58 miles per hour ). Until then, Edmund Fitzgerald had followed Arthur M. Anderson, which was travelling at a changeless 14.6 miles per hour ( 12.7 kn ; 23.5 kilometers per hour ), but the faster Edmund Fitzgerald pulled ahead at about 3:00 ante meridiem As the storm center passed over the ships, they experienced shifting winds, with tip speeds temporarily dropping as wreathe direction changed from northeast to south and then northwest. After 1:50 post meridiem, when Arthur M. Anderson logged winds of 50 knots ( 93 kilometers per hour ; 58 miles per hour ), wind speeds again picked up quickly, and it began to snow at 2:45 post meridiem, reducing visibility ; Arthur M. Anderson lost sight of Edmund Fitzgerald, which was about 16 miles ( 26 kilometer ) ahead at the time. shortly after 3:30 post meridiem, Captain McSorley radioed Arthur M. Anderson to report that Edmund Fitzgerald was taking on urine and had lost two vent covers and a fence railing. The vessel had besides developed a list. Two of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s six bilge pumps ran continuously to discharge ship water. McSorley said that he would slow his transport down so that Arthur M. Anderson could close the gap between them. In a broadcast shortly subsequently, the United States Coast Guard ( USCG ) warned all ship that the Soo Locks had been closed and they should seek safe anchorage. concisely after 4:10 post meridiem, McSorley called Arthur M. Anderson again to report a radar failure and asked Arthur M. Anderson to keep racetrack of them. Edmund Fitzgerald, efficaciously blind, slowed to let Arthur M. Anderson come within a 10-mile ( 16 kilometer ) crop so she could receive radar steering from the other ship. For a fourth dimension, Arthur M. Anderson directed Edmund Fitzgerald toward the relative condom of Whitefish Bay ; then, at 4:39 post meridiem, McSorley contacted the USCG station in Grand Marais, Michigan, to inquire whether the whitefish Point light and navigation beacon were operational. The USCG replied that their monitor equipment indicated that both instruments were dormant. McSorley then hailed any ships in the whitefish Point area to report the state of the navigational aids, receiving an answer from Captain Cedric Woodard of Avafors between 5:00 and 5:30 post meridiem that the whitefish Point light was on but not the radio beacon. Woodard testified to the Marine Board that he overheard McSorley say, “ Do n’t allow cipher on deck, ” angstrom well as something about a vent that Woodard could not understand. Some prison term belated, McSorley told Woodard, “ I have a ‘bad tilt ‘, I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst sea I have ever been in. ” By late in the good afternoon of November 10, sustained winds of over 50 knots ( 93 kilometers per hour ; 58 miles per hour ) were recorded by ships and observation points across easterly Lake Superior. Arthur M. Anderson logged confirm winds a gamey as 58 knots ( 107 kilometers per hour ; 67 miles per hour ) at 4:52 post meridiem, while waves increased to equally high as 25 feet ( 7.6 thousand ) by 6:00 p.m. Arthur M. Anderson was besides struck by 70-to-75-knot ( 130 to 139 km/h ; 81 to 86 miles per hour ) gusts and rogue waves american samoa high as 35 feet ( 11 megabyte ). At approximately 7:10 post meridiem, when Arthur M. Anderson notified Edmund Fitzgerald of an upbound ship and asked how she was doing, McSorley reported, “ We are holding our own. ” She was never heard from again. No distress sign was received, and ten minutes belated, Arthur M. Anderson lost the ability either to reach Edmund Fitzgerald by radio receiver or to detect her on radar .

Map showing the location of the wreck Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin, at 2:15 post meridiem on the good afternoon of November 9, 1975, under the command of Captain Ernest M. McSorley. She was en path to the steel mill on Zug Island, near Detroit, Michigan, with a cargo of 26,116 long tons ( 29,250 short-circuit tons ; 26,535 thymine ) of taconite ore pellets and soon reached her full travel rapidly of 16.3 miles per hour ( 14.2 kn ; 26.2 kilometers per hour ). Around 5 post meridiem, Edmund Fitzgerald joined a moment bottom under the command of Captain Jesse B. “ Bernie ” Cooper, Arthur M. Anderson, destined for Gary, Indiana, out of Two Harbors, Minnesota. The upwind prognosis was not unusual for November and the National Weather Service ( NWS ) predicted that a storm would pass just south of Lake Superior by 7 ante meridiem on November 10. SS Wilfred Sykes loaded opposite Edmund Fitzgerald at the Burlington Northern Dock # 1 and departed at 4:15 post meridiem, about two hours after Edmund Fitzgerald. In contrast to the NWS prognosis, Captain Dudley J. Paquette of Wilfred Sykes predicted that a major ramp would directly cross Lake Superior. From the beginning, he chose a path that took advantage of the protection offered by the lake ‘s north shore to avoid the worst effects of the storm. The crew of Wilfred Sykes followed the radio conversations between Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur M. Anderson during the foremost separate of their trip and overheard their captains deciding to take the even Lake Carriers ‘ Association downbound route. The NWS altered its forecast at 7:00 post meridiem, issuing gale warnings for the whole of Lake Superior. Arthur M. Anderson and Edmund Fitzgerald altered naturally northbound seeking protection along the Ontario shore where they encountered a winter storm at 1:00 ante meridiem on November 10. Edmund Fitzgerald reported winds of 52 knots ( 96 kilometers per hour ; 60 miles per hour ) and waves 10 feet ( 3.0 meter ) high. Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes reported that after 1 ante meridiem, he overheard McSorley say that he had reduced the ship ‘s speed because of the rocky conditions. Paquette said he was stunned to later hear McSorley, who was not known for turning aside or slowing down, state that “ we ‘re going to try for some lee from Isle Royale. You ‘re walking off from us anyhow … I ca n’t stay with you. ” At 2:00 ante meridiem on November 10, the NWS upgraded its warnings from gale to storm, forecasting winds of 35–50 knots ( 65–93 kilometers per hour ; 40–58 miles per hour ). Until then, Edmund Fitzgerald had followed Arthur M. Anderson, which was travelling at a changeless 14.6 miles per hour ( 12.7 kn ; 23.5 kilometers per hour ), but the faster Edmund Fitzgerald pulled ahead at about 3:00 ante meridiem As the storm center passed over the ships, they experienced shifting winds, with tip speeds temporarily dropping as wreathe direction changed from northeast to south and then northwest. After 1:50 post meridiem, when Arthur M. Anderson logged winds of 50 knots ( 93 kilometers per hour ; 58 miles per hour ), wind speeds again picked up quickly, and it began to snow at 2:45 post meridiem, reducing visibility ; Arthur M. Anderson lost sight of Edmund Fitzgerald, which was about 16 miles ( 26 kilometer ) ahead at the time. shortly after 3:30 post meridiem, Captain McSorley radioed Arthur M. Anderson to report that Edmund Fitzgerald was taking on urine and had lost two vent covers and a fence railing. The vessel had besides developed a list. Two of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s six bilge pumps ran continuously to discharge ship water. McSorley said that he would slow his transport down so that Arthur M. Anderson could close the gap between them. In a broadcast shortly subsequently, the United States Coast Guard ( USCG ) warned all ship that the Soo Locks had been closed and they should seek safe anchorage. concisely after 4:10 post meridiem, McSorley called Arthur M. Anderson again to report a radar failure and asked Arthur M. Anderson to keep racetrack of them. Edmund Fitzgerald, efficaciously blind, slowed to let Arthur M. Anderson come within a 10-mile ( 16 kilometer ) crop so she could receive radar steering from the other ship. For a fourth dimension, Arthur M. Anderson directed Edmund Fitzgerald toward the relative condom of Whitefish Bay ; then, at 4:39 post meridiem, McSorley contacted the USCG station in Grand Marais, Michigan, to inquire whether the whitefish Point light and navigation beacon were operational. The USCG replied that their monitor equipment indicated that both instruments were dormant. McSorley then hailed any ships in the whitefish Point area to report the state of the navigational aids, receiving an answer from Captain Cedric Woodard of Avafors between 5:00 and 5:30 post meridiem that the whitefish Point light was on but not the radio beacon. Woodard testified to the Marine Board that he overheard McSorley say, “ Do n’t allow cipher on deck, ” angstrom well as something about a vent that Woodard could not understand. Some prison term belated, McSorley told Woodard, “ I have a ‘bad tilt ‘, I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst sea I have ever been in. ” By late in the good afternoon of November 10, sustained winds of over 50 knots ( 93 kilometers per hour ; 58 miles per hour ) were recorded by ships and observation points across easterly Lake Superior. Arthur M. Anderson logged confirm winds a gamey as 58 knots ( 107 kilometers per hour ; 67 miles per hour ) at 4:52 post meridiem, while waves increased to equally high as 25 feet ( 7.6 thousand ) by 6:00 p.m. Arthur M. Anderson was besides struck by 70-to-75-knot ( 130 to 139 km/h ; 81 to 86 miles per hour ) gusts and rogue waves american samoa high as 35 feet ( 11 megabyte ). At approximately 7:10 post meridiem, when Arthur M. Anderson notified Edmund Fitzgerald of an upbound ship and asked how she was doing, McSorley reported, “ We are holding our own. ” She was never heard from again. No distress sign was received, and ten minutes belated, Arthur M. Anderson lost the ability either to reach Edmund Fitzgerald by radio receiver or to detect her on radar .

search [edit ]

Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s lifeboats, on display at the Valley Camp museum ship One ofs lifeboats, on display at themuseum ship Captain Cooper of Arthur M. Anderson beginning called the USCG in Sault Ste. Marie at 7:39 post meridiem on distribution channel 16, the radio straiten frequency. The USCG responders instructed him to call back on groove 12 because they wanted to keep their emergency distribution channel open and they were having difficulty with their communication systems, including antennas blown down by the storm. Cooper then contacted the upbound seawater vessel Nanfri and was told that she could not pick up Edmund Fitzgerald on her radar either. Despite repeated attempts to raise the USCG, Cooper was not successful until 7:54 post meridiem when the military officer on duty asked him to keep lookout for a 16-foot ( 4.9 molarity ) boat lost in the area. At about 8:25 post meridiem, Cooper again called the USCG to express his business about Edmund Fitzgerald and at 9:03 post meridiem reported her neglect. junior-grade Officer Philip Branch belated testified, “ I considered it good, but at the time it was not pressing. ” Lacking allow search-and-rescue vessels to respond to Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s catastrophe, at approximately 9:00 post meridiem, the USCG asked Arthur M. Anderson to turn around and look for survivors. Around 10:30 post meridiem, the USCG asked all commercial vessels anchored in or near whitefish Bay to assist in the search. The initial search for survivors was carried out by Arthur M. Anderson, and a second bottom, SS William Clay Ford. The efforts of a third bottom, the Toronto -registered SS Hilda Marjanne, were foiled by the weather. The USCG sent a buoy sensitive, Woodrush, from Duluth, Minnesota, but it took two and a half hours to launch and a day to travel to the research area. The Traverse City, Michigan, USCG post launched an HU-16 fixed-wing search aircraft that arrived on the scenery at 10:53 post meridiem while an HH-52 USCG helicopter with a 3.8-million- candlepower searchlight arrived at 1:00 ante meridiem on November 11. canadian Coast Guard aircraft joined the three-day search and the Ontario Provincial Police established and maintained a beach patrol all along the easterly land of Lake Superior. Although the research recovered debris, including lifeboats and rafts, none of the gang were found. On her final voyage, Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s crew of 29 consisted of the captain ; the first base, second, and third base mates ; five engineers ; three oilers ; a cook ; a wiper ; two alimony men ; three watchmen ; three deckhands ; three wheelsmen ; two porters ; a cadet ; and a steward. Most of the crowd were from Ohio and Wisconsin ; their ages ranged from 20 ( watchman Karl A. Peckol ) to 63 ( Captain McSorley ). Edmund Fitzgerald is among the largest and best-known vessels lost on the Great Lakes, but she is not alone on the Lake Superior seabed in that area. In the years between 1816, when Invincible was lost, and 1975, when Edmund Fitzgerald sank, the whitefish Point sphere had claimed at least 240 ships .

Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s lifeboats, on display at the Valley Camp museum ship One ofs lifeboats, on display at themuseum ship Captain Cooper of Arthur M. Anderson beginning called the USCG in Sault Ste. Marie at 7:39 post meridiem on distribution channel 16, the radio straiten frequency. The USCG responders instructed him to call back on groove 12 because they wanted to keep their emergency distribution channel open and they were having difficulty with their communication systems, including antennas blown down by the storm. Cooper then contacted the upbound seawater vessel Nanfri and was told that she could not pick up Edmund Fitzgerald on her radar either. Despite repeated attempts to raise the USCG, Cooper was not successful until 7:54 post meridiem when the military officer on duty asked him to keep lookout for a 16-foot ( 4.9 molarity ) boat lost in the area. At about 8:25 post meridiem, Cooper again called the USCG to express his business about Edmund Fitzgerald and at 9:03 post meridiem reported her neglect. junior-grade Officer Philip Branch belated testified, “ I considered it good, but at the time it was not pressing. ” Lacking allow search-and-rescue vessels to respond to Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s catastrophe, at approximately 9:00 post meridiem, the USCG asked Arthur M. Anderson to turn around and look for survivors. Around 10:30 post meridiem, the USCG asked all commercial vessels anchored in or near whitefish Bay to assist in the search. The initial search for survivors was carried out by Arthur M. Anderson, and a second bottom, SS William Clay Ford. The efforts of a third bottom, the Toronto -registered SS Hilda Marjanne, were foiled by the weather. The USCG sent a buoy sensitive, Woodrush, from Duluth, Minnesota, but it took two and a half hours to launch and a day to travel to the research area. The Traverse City, Michigan, USCG post launched an HU-16 fixed-wing search aircraft that arrived on the scenery at 10:53 post meridiem while an HH-52 USCG helicopter with a 3.8-million- candlepower searchlight arrived at 1:00 ante meridiem on November 11. canadian Coast Guard aircraft joined the three-day search and the Ontario Provincial Police established and maintained a beach patrol all along the easterly land of Lake Superior. Although the research recovered debris, including lifeboats and rafts, none of the gang were found. On her final voyage, Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s crew of 29 consisted of the captain ; the first base, second, and third base mates ; five engineers ; three oilers ; a cook ; a wiper ; two alimony men ; three watchmen ; three deckhands ; three wheelsmen ; two porters ; a cadet ; and a steward. Most of the crowd were from Ohio and Wisconsin ; their ages ranged from 20 ( watchman Karl A. Peckol ) to 63 ( Captain McSorley ). Edmund Fitzgerald is among the largest and best-known vessels lost on the Great Lakes, but she is not alone on the Lake Superior seabed in that area. In the years between 1816, when Invincible was lost, and 1975, when Edmund Fitzgerald sank, the whitefish Point sphere had claimed at least 240 ships .

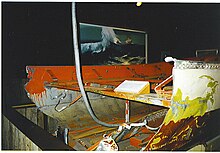

Wreck discovery and surveys [edit ]

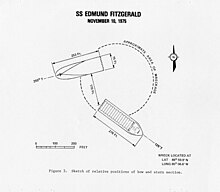

A USCG draw of the relative positions of the wreck parts

A USCG draw of the relative positions of the wreck parts

Wreck discovery [edit ]

A U.S. Navy Lockheed P-3 Orion aircraft, piloted by Lt. George Conner and equipped to detect charismatic anomalies normally associated with submarines, found the wreck on November 14, 1975. Edmund Fitzgerald put about 15 miles ( 13 nmi ; 24 kilometer ) west of Deadman ‘s Cove, Ontario ( about 8 miles ( 7.0 nmi ; 13 kilometer ) northwest of Pancake Bay Provincial Park ), 17 miles ( 15 nmi ; 27 kilometer ) from the capture to Whitefish Bay to the southeast, in canadian waters close up to the international boundary at a depth of 530 feet ( 160 thousand ). A foster November 14–16 view by the USCG using a side scan sonar revealed two large objects lying conclude together on the lake floor. The U.S. Navy besides contracted Seaward, Inc., to conduct a moment review between November 22 and 25 .

Underwater surveys [edit ]

From May 20 to 28, 1976, the U.S. Navy dived on the crash using its unmanned submersible, CURV-III, and found Edmund Fitzgerald lying in two large pieces in 530 feet ( 160 thousand ) of water. Navy estimates put the duration of the crouch section at 276 feet ( 84 m ) and that of the stern section at 253 feet ( 77 megabyte ). The bow department stood upright in the mud, some 170 feet ( 52 m ) from the austere section that lay capsized at a 50-degree angle from the bow. In between the two break sections lay a boastfully mass of taconite pellets and scatter wreckage lying approximately, including brood covers and hull plate. In 1980, during a Lake Superior research dive expedition, marine explorer Jean-Michel Cousteau, the son of Jacques Cousteau, sent two divers from RV Calypso in the inaugural manned submersible dive to Edmund Fitzgerald. The dive was brief, and although the dive team drew no final conclusions, they speculated that Edmund Fitzgerald had broken up on the come on. The Michigan Sea Grant Program organized a three-day dive to surveil Edmund Fitzgerald in 1989. The primary objective was to record three-d videotape for function in museum educational programs and the product of documentaries. The dispatch used a towed survey organization ( TSS Mk1 ) and a automotive, tethered, free-swimming remotely function subaqueous fomite ( ROV ). The Mini Rover ROV was equipped with miniature stereoscopic cameras and fisheye lenses in orderliness to produce three-d images. The towed survey system and the Mini Rover ROV were designed, built and operated by Chris Nicholson of Deep Sea Systems International, Inc. Participants included the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ( NOAA ), the National Geographic Society, the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society ( GLSHS ), and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the latter providing RV Grayling as the corroborate vessel for the ROV. The GLSHS used part of the five hours of video footage produced during the dives in a documentary and the National Geographic Society used a section in a circulate. Frederick Stonehouse, who wrote one of the first books on the Edmund Fitzgerald shipwreck, moderated a 1990 empanel revue of the video that drew no conclusions about the cause of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s sink. canadian explorer Joseph B. MacInnis organized and led six publicly funded dives to Edmund Fitzgerald over a three-day menstruation in 1994. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution provided Edwin A. Link as the support vessel, and their manned submersible, Celia. The GLSHS paid $ 10,000 for three of its members to each join a dive and take calm pictures. MacInnis concluded that the notes and television obtained during the dives did not provide an explanation why Edmund Fitzgerald sink. The same class, longtime sport diver Fred Shannon formed Deepquest Ltd., and organized a privately funded dive to the shipwreck of Edmund Fitzgerald, using Delta Oceanographic ‘s submersible, Delta. Deepquest Ltd. conducted seven dives and took more than 42 hours of submerged video recording while Shannon set the record for the longest submersible dive to Edmund Fitzgerald at 211 minutes. Prior to conducting the dives, Shannon studied NOAA navigational charts and found that the international boundary had changed three times before its publication by NOAA in 1976. Shannon determined that based on GPS coordinates from the 1994 Deepquest expedition, “ at least one-third of the two acres of immediate wreckage containing the two major portions of the vessel is in U.S. waters because of an error in the put of the U.S.–Canada limit channel shown on official lake charts. ” Shannon ‘s group discovered the remains of a gang member partially dressed in coveralls and wearing a life jacket lying face up on the lake bottom alongside the bow of the embark, indicating that at least one of the crowd was aware of the possibility of sinking. The life jacket had deteriorated canvas and “ what is thought to be six rectangular cork blocks … intelligibly visible. ” Shannon concluded that “ massive and advancing structural failure ” caused Edmund Fitzgerald to break apart on the come on and sink. MacInnis led another series of dives in 1995 to salvage the bell from Edmund Fitzgerald. The Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians backed the dispatch by co-signing a lend in the amount of $ 250,000. [ 87 ] canadian engineer Phil Nuytten ‘s atmospheric diving suit, known as the “ Newtsuit, ” was used to retrieve the bell from the embark, replace it with a replica, and put a beer can in Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s pilothouse. That lapp year, Terrence Tysall and Mike Zee set multiple records when they used trimix gas to scuba dive to Edmund Fitzgerald. The pair are the merely people known to have touched the Edmund Fitzgerald wreck. They besides set records for the deepest aqualung dive on the Great Lakes and the deepest shipwreck dive, and were the first divers to reach Edmund Fitzgerald without the help of a submersible. It took six minutes to reach the bust up, six minutes to review it, and three hours to resurface to avoid decompression illness, besides known as “ the bends. ”

Restrictions on surveys [edit ]

Under the Ontario Heritage Act, activities on registered archaeological sites require a license. In March 2005, the whitefish Point Preservation Society accused the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society ( GLSHS ) of conducting an unauthorized prima donna to Edmund Fitzgerald. Although the director of the GLSHS admitted to conducting a sonar scan of the crash in 2002, he denied such a survey required a license at the time it was carried out. An April 2005 amendment to the Ontario Heritage Act allows the Ontario government to impose a license prerequisite on dives, the operation of submersibles, side scan sonars or subaqueous cameras within a delegate radius about protected sites. Conducting any of those activities without a license would result in fines of up to CA $ 1 million. On the basis of the amended police, to protect wreck sites considered “ watery graves ”, the Ontario government issued update regulations in January 2006, including an area with a 500-meter ( 1,640 foot ) radius around Edmund Fitzgerald and other specifically designated marine archaeological sites. In 2009, a further amendment to the Ontario Heritage Act imposed license requirements on any type of surveying device .

Hypotheses on the cause of sinking [edit ]

Extreme weather and ocean conditions play a function in all of the published hypotheses regarding Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s sinking, but they differ on the other causal factors .

Waves and weather hypothesis [edit ]

In 2005, NOAA and the NWS ran a calculator pretense, including weather and brandish conditions, covering the period from November 9, 1975, until the early dawn of November 11. analysis of the simulation showed that two separate areas of eminent fart appeared over Lake Superior at 4:00 post meridiem on November 10. One had speeds in surfeit of 43 knots ( 80 kilometers per hour ; 49 miles per hour ) and the early winds in excess of 40 knots ( 74 kilometers per hour ; 46 miles per hour ). The southeast separate of the lake, the guidance in which Edmund Fitzgerald was heading, had the highest winds. average wave heights increased to near 19 feet ( 5.8 thousand ) by 7:00 post meridiem, November 10, and winds exceeded 50 miles per hour ( 43 kn ; 80 kilometers per hour ) over most of southeastern Lake Superior. Edmund Fitzgerald sink at the eastern border of the area of high wind where the long fetch, or distance that wreathe blows over water, produced significant waves averaging over 23 feet ( 7.0 megabyte ) by 7:00 post meridiem and over 25 feet ( 7.6 megabyte ) at 8:00 p.m. The pretense besides showed one in 100 waves reaching 36 feet ( 11 m ) and one knocked out of every 1,000 reaching 46 feet ( 14 meter ). Since the transport was heading east-southeastward, it is likely that the waves caused Edmund Fitzgerald to roll heavily. At the fourth dimension of the sinking, the ship Arthur M. Anderson reported northwest winds of 57 miles per hour ( 50 kn ; 92 kilometers per hour ), matching the simulation analysis resultant role of 54 miles per hour ( 47 kn ; 87 kilometers per hour ). The analysis far showed that the maximum sustained winds reached near hurricane force of about 70 miles per hour ( 61 kn ; 110 kilometers per hour ) with gusts to 86 miles per hour ( 75 kn ; 138 kilometers per hour ) at the time and placement where Edmund Fitzgerald slump .

Rogue wave hypothesis [edit ]

A group of three rogue waves, much called “ three sisters, ” was reported in the vicinity of Edmund Fitzgerald at the meter she sank. The “ three sisters ” phenomenon is said to occur on Lake Superior as a result of a sequence of three rogue waves forming that are one-third larger than normal waves. The first wave introduces an abnormally large come of water onto the deck. This water is unable to amply drain away before the moment wave strikes, adding to the excess. The third entrance wave again adds to the two accumulate backwashes, quickly overloading the deck with besides much water. Captain Cooper of Arthur M. Anderson reported that his ship was “ hit by two 30 to 35 animal foot seas about 6:30 post meridiem, one burying the aft cabins and damaging a lifeboat by pushing it right down onto the saddle. The second base wave of this size, possibly 35 foot, came over the bridge deck. ” Cooper went on to say that these two waves, possibly followed by a third, continued in the direction of Edmund Fitzgerald and would have struck about the meter she sank. This hypothesis postulates that the “ three sisters ” compounded the counterpart problems of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s know list and her lower speed in heavy seas that already allowed water to remain on her deck for longer than common. The “ Edmund Fitzgerald “ episode of the 2010 television receiver series Dive Detectives features the wave-generating tank of the National Research Council ‘s Institute for Naval Technology in St. John ‘s, and the tank ‘s model of the effect of a 17-meter ( 56 foot ) rogue wave upon a scale model of Edmund Fitzgerald. The pretense indicated such a rogue curl could about wholly submerge the bow or stern of the ship with body of water, at least temporarily .

Cargo-hold implosion therapy guess [edit ]

The July 26, 1977, USCG Marine Casualty Report suggested that the accident was caused by ineffective hatch closures. The report concluded that these devices failed to prevent waves from inundating the cargo control. The flood occurred gradually and probably imperceptibly throughout the final examination day, ultimately resulting in a fatal loss of airiness and constancy. As a solution, Edmund Fitzgerald plummeted to the bed without warning. Video footage of the wreck web site showed that most of her think up clamps were in perfect condition. The USCG Marine circuit board concluded that the few damaged clamps were probably the lone ones fastened. As a leave, ineffective think up settlement caused Edmund Fitzgerald to flood and founder. From the begin of the USCG inquiry, some of the crewmen ‘s families and assorted parturiency organizations believed the USCG findings could be tainted because there were good questions regarding their readiness american samoa well as license and rules changes. Paul Trimble, a retire USCG frailty admiral and president of the united states of the Lake Carriers Association ( LCA ), wrote a letter to the National Transportation Safety Board ( NTSB ) on September 16, 1977, that included the follow statements of objection to the USCG findings :

The salute hatch covers are an advance design and are considered by the entire lake embark industry to be the most significant improvement over the telescoping leaf covers previously used for many years … The one-piece think up covers have proven wholly satisfactory in all weather conditions without a single vessel personnel casualty in about 40 years of use … and no water accumulation in cargo holds …

It was common commit for ore freighters, even in afoul weather, to embark with not all cargo clamps locked in place on the hatch covers. Maritime generator Wolff reported that depending on weather conditions, all the clamps were finally set within one to two days. Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes was dismissive of suggestions that unlocked hatch clamps caused Edmund Fitzgerald to laminitis. He said that he normally sailed in fine weather using the minimal numeral of clamps necessity to secure the think up covers. The May 4, 1978, NTSB findings differed from the USCG. The NTSB made the take after observations based on the CURV-III sketch :

The No. 1 hatch cover was wholly inside the No. 1 hatch and showed indications of buckling from external load. Sections of the coaming in direction of the No. 1 hatch were fractured and buckled inward. The No. 2 hatch brood was missing and the coaming on the No. 2 hatch was fractured and buckled. Hatches Nos. 3 and 4 were covered with mud ; one corner of hatch cover No. 3 could be seen in stead. Hatch cover No. 5 was missing. A series of 16 consecutive hatch cover clamps were observed on the No. 5 hatch coaming. Of this series, the beginning and eighth were distorted or broken. All of the 14 early clamps were undamaged and in the open position. The No. 6 hatch was receptive and a hatch brood was standing on end vertically in the hatch. The hatch covers were missing from hatches Nos. 7 and 8 and both coamings were fractured and sternly distorted. The bow incision abruptly ended just aft of think up No. 8 and the deck plate was ripped up from the separation to the forward conclusion of hatch No. 7.

Read more: How Maritime Law Works

The NTSB conducted calculator studies, testing and psychoanalysis to determine the forces necessary to collapse the brood covers and concluded that Edmund Fitzgerald sank suddenly from flooding of the cargo apply “ due to the collapse of one or more of the hatch covers under the weight of giant boarding seas ” rather of flooding gradually due to ineffective hatch closures. The NTSB dissenting opinion held that Edmund Fitzgerald sank suddenly and unexpectedly from shoaling .

Shoaling hypothesis [edit ]

The LCA believed that rather of hatch cover escape, the more probable cause of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s loss was shoaling or grounding in the Six Fathom Shoal northwest of Caribou Island when the vessel “ unwittingly raked a reef “ during the meter the whitefish Point unhorse and radio beacon were not available as navigation aids. This hypothesis was supported by a 1976 canadian hydrographic review, which disclosed that an stranger school ran a mile farther east of Six Fathom Shoal than shown on the canadian charts. Officers from Arthur M. Anderson observed that Edmund Fitzgerald sailed through this exact sphere. guess by proponents of the Six Fathom Shoal guess concluded that Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s toss off fence rail reported by McSorley could occur only if the transport “ hogged “ during shallow, with the bow and austere bent downward and the middle raised by the shoal, pulling the railing tight until the cables dislodged or tore under the form. Divers searched the Six Fathom Shoal after the crash occurred and found no tell of “ a recent collision or ground anywhere. ” nautical authors Bishop and Stonehouse wrote that the shoaling hypothesis was late challenged on the footing of the higher quality of detail in Shannon ‘s 1994 photography that “ explicitly show [ sulfur ] the devastation of the Edmund Fitzgerald “. Shannon ‘s photography of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s overthrow buttocks showed “ no evidence on the bottom of the austere, the propeller or the rudder of the transport that would indicate the ship struck a shallow. ” Maritime author Stonehouse reasoned that “ unlike the Lake Carriers, the Coast Guard had no vested interest in the consequence of their probe. ” writer Bishop reported that Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes argued that through their corroborate for the shallow explanation, the LCA represented the transportation caller ‘s interests by advocating a hypothesis that held LCA member companies, the American Bureau of Shipping, and the U.S. Coast Guard Service blameless. Paul Hainault, a retire professor of mechanical mastermind from Michigan Technological University, promoted a hypothesis that began as a student course project. His hypothesis held that Edmund Fitzgerald grounded at 9:30 ante meridiem on November 10 on ranking Shoal. This shoal, charted in 1929, is an subaqueous mountain in the center of Lake Superior about 50 miles ( 80 kilometer ) north of Copper Harbor, Michigan. It has sharp peaks that rise closely to the lake surface with water depths ranging from 22 to 400 feet ( 6.7 to 121.9 megabyte ), making it a menace to navigation. Discovery of the shallow resulted in a change in recommend ship routes. A seiche, or standing wave, that occurred during the low-pressure system over Lake Superior on November 10, 1975, caused the lake to rise 3 feet ( 0.91 thousand ) over the Soo Locks ‘s gates to flood Portage Avenue in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, with 1 metrical foot ( 0.3 meter ) of water. Hainault ‘s hypothesis held that this seiche contributed to Edmund Fitzgerald shoaling 200 feet ( 61 thousand ) of her hull on Superior Shoal, causing the hull to be punctured mid-body. The hypothesis contended that the wave action continued to damage the hull, until the middle one-third dropped out like a box, leaving the ship held together by the concentrate deck. The austere section acted as an anchor and caused Edmund Fitzgerald to come to a full diaphragm, causing everything to go advancing. The ship broke apart on the surface within seconds. Compressed air out coerce blew a hole in the starboard bow, which sank 18 degrees off course. The rear kept going forward with the engine inactive running, rolled to port and landed bottom up .

geomorphologic failure hypothesis [edit ]

Another published hypothesis contends that an already weakened structure, and change of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s winter cargo line ( which allows heavier loading and travel lower in the water ), made it possible for bombastic waves to cause a stress fracture in the hull. This is based on the “ regular ” huge waves of the storm and does not inevitably involve rogue waves. The USCG and NTSB investigated whether Edmund Fitzgerald broke apart due to geomorphologic failure of the hull and because the 1976 CURV III survey found Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s sections were 170 feet ( 52 thousand ) from each other, the USCG ‘s conventional fatal accident report of July 1977 concluded that she had separated upon hitting the lake floor. The NTSB came to the like decision as USCG because :

The proximity of the bow and buttocks sections on the bottom of Lake Superior indicated that the vessel sink in one piece and broke apart either when it hit bottom or as it descended. Therefore, Edmund Fitzgerald did not sustain a massive structural bankruptcy of the hull while on the surface … The final position of the wreckage indicated that if the Edmund Fitzgerald had capsized, it must have suffered a structural bankruptcy before hitting the lake bottom. The bow section would have had to right itself and the austere helping would have had to capsize before coming to rest on the bottom. It is, therefore, concluded that the Edmund Fitzgerald did not capsize on the surface .

other authors have concluded that Edmund Fitzgerald most likely break in two on the surface before sinking due to the intense waves, like the ore carriers SS Carl D. Bradley and SS Daniel J. Morrell. [ 126 ] [ 127 ] [ 128 ] After nautical historian Frederick Stonehouse moderated the panel reviewing the video recording footage from the 1989 ROV survey of Edmund Fitzgerald, he concluded that the extent of taconite coverage over the shipwreck locate showed that the stern had floated on the open for a short time and spilled taconite into the forward section ; therefore the two sections of the crash did not sink at the like time. The 1994 Shannon team found that the austere and the bow were 255 feet ( 78 thousand ) apart, leading Shannon to conclude that Edmund Fitzgerald broke up on the surface. He said :

This placement does not support the hypothesis that the ship plunged to the bottom in one piece, breaking apart when it struck bed. If this were truthful, the two sections would be much closer. In summation, the fish, repose and mound of clay and mud at the locate indicate the stern rolled over on the coat, spilling taconite ore pellets from its severed cargo prevail, and then landed on portions of the cargo itself .

The stress fracture guess was supported by the testimony of erstwhile crewmen. Former Second Mate Richard Orgel, who served on Edmund Fitzgerald in 1972 and 1973, testified that “ the ship had a tendency to bend and spring during storms ‘like a diving board after person has jumped off. ‘ ” Orgel was quoted as saying that the loss of Edmund Fitzgerald was caused by hull failure, “ pure and simple. I detected undue stress in the side tunnels by examining the whiten enamel key, which will crack and splinter when submitted to severe stress. ” George H. “ Red ” Burgner, Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s shop steward for ten seasons and winter ship-keeper for seven years, testified in a deposit that a “ loose keel “ contributed to the vessel ‘s loss. Burgner far testified that “ the keel and sister kelsons were only ‘tack welded ‘ ” and that he had personally observed that many of the welds were broken. Burgner was not asked to testify before the Marine Board of Inquiry. When Bethlehem Steel Corporation permanently laid up Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s sister embark, SS Arthur B. Homer, merely five years after going to considerable expense to lengthen her, questions were raised as to whether both ships had the lapp structural problems. The two vessels were built in the like shipyard using welded joints rather of the rivet joints used in older ore freighters. Riveted joints allow a ship to flex and work in heavy seas, while welded joints are more likely to break. Reports indicate that repairs to Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s hull were delayed in 1975 due to plans to lengthen the transport during the approaching winter lay-up. Arthur B. Homer was lengthened to 825 feet ( 251 meter ) and placed back in service by December 1975, not retentive after Edmund Fitzgerald foundered. In 1978, without explanation, Bethlehem Steel Corporation denied permission for the president of the NTSB to travel on Arthur B. Homer. Arthur B. Homer was permanently laid up in 1980 and broken for scrap in 1987. Retired GLEW naval architect Raymond Ramsay, one of the members of the invention team that worked on the hull of Edmund Fitzgerald, reviewed her increased lode lines, sustenance history, along with the history of long ship hull failure and concluded that Edmund Fitzgerald was not seaworthy on November 10, 1975. He stated that planning Edmund Fitzgerald to be compatible with the constraints of the St. Lawrence Seaway had placed her hull design in a “ straight jacket [ sic? ]. ” Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s long-ship design was developed without the benefit of research, growth, examination, and evaluation principles while computerize analytic engineering was not available at the time she was built. Ramsay noted that Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s hull was built with an all-welded ( rather of riveted ) modular fabrication method, which was used for the inaugural time in the GLEW shipyard. Ramsay concluded that increasing the hull distance to 729 feet ( 222 megabyte ) resulted in an L/D slenderness ratio ( the ratio of the length of the ship to the astuteness of her structure ) that caused excessive multi-axial bend and bounce of the hull, and that the hull should have been structurally reinforced to cope with her increased length .

Topside damage hypothesis [edit ]

The USCG cited topside price as a reasonable alternative reason for Edmund Fitzgerald slump and surmised that wrong to the fence rail and vents was possibly caused by a heavy floating object such as a log. historian and mariner Mark Thompson believes that something broke loose from Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s deck. He theorized that the loss of the vents resulted in flood of two ballast tanks or a ballast tank and a walk tunnel that caused the ship to list. Thompson promote conjectured that price more across-the-board than Captain McSorley could detect in the pilothouse let water flood the cargo oblige. He concluded that the topside damage Edmund Fitzgerald experienced at 3:30 post meridiem on November 10, compounded by the arduous seas, was the most obvious explanation for why she sank .

possible put up factors [edit ]

The USCG, NTSB, and proponents of option theories have all named multiple potential contributing factors to the fall through of Edmund Fitzgerald .

Weather forecasting [edit ]

Edmund Fitzgerald A scale model of SS The NWS long-range forecast on November 9, 1975, predicted that a storm would pass barely south of Lake Superior and over the Keweenaw Peninsula, extending into the Lake from Michigan ‘s Upper Peninsula. Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes had been following and charting the low-pressure system over Oklahoma since November 8 and concluded that a major ramp would track across eastern Lake Superior. He therefore chose a route that gave Wilfred Sykes the most protection and took recourse in Thunder Bay, Ontario, during the worst of the storm. Based on the NWS prognosis, Arthur M. Anderson and Edmund Fitzgerald rather started their trip across Lake Superior following the regular Lake Carriers Association path, which placed them in the path of the storm. The NTSB investigation concluded that the NWS failed to accurately bode wave heights on November 10. After running calculator models in 2005 using actual meteorologic data from November 10, 1975, Hultquist of the NWS said of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s status in the storm, “ It ended in precisely the faulty rate at the absolute worst time. ”

Edmund Fitzgerald A scale model of SS The NWS long-range forecast on November 9, 1975, predicted that a storm would pass barely south of Lake Superior and over the Keweenaw Peninsula, extending into the Lake from Michigan ‘s Upper Peninsula. Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes had been following and charting the low-pressure system over Oklahoma since November 8 and concluded that a major ramp would track across eastern Lake Superior. He therefore chose a route that gave Wilfred Sykes the most protection and took recourse in Thunder Bay, Ontario, during the worst of the storm. Based on the NWS prognosis, Arthur M. Anderson and Edmund Fitzgerald rather started their trip across Lake Superior following the regular Lake Carriers Association path, which placed them in the path of the storm. The NTSB investigation concluded that the NWS failed to accurately bode wave heights on November 10. After running calculator models in 2005 using actual meteorologic data from November 10, 1975, Hultquist of the NWS said of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s status in the storm, “ It ended in precisely the faulty rate at the absolute worst time. ”

Inaccurate navigational charts [edit ]

After reviewing testimony that Edmund Fitzgerald had passed near shoals north of Caribou Island, the USCG Marine Board examined the relevant navigational charts. They found that the canadian 1973 navigational chart for the Six Fathom Shoal area was based on canadian surveys from 1916 and 1919 and that the 1973 U.S. Lake Survey Chart No. 9 included the notation, “ canadian Areas. For data concerning canadian areas, canadian authorities have been consulted. ” thereafter, at the request of the Marine Board and the Commander of the USCG Ninth District, the Canadian Hydrographic Service conducted a survey of the area surrounding Michipicoten Island and Caribou Island in 1976. The view revealed that the shoal ran about 1 mile ( 1.6 kilometer ) farther east than shown on canadian charts. The NTSB investigation concluded that, at the clock of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s foundering, Lake Survey Chart No. 9 was not detailed adequate to indicate Six Fathom Shoal as a venture to seafaring .

lack of watertight bulkheads [edit ]

Mark Thompson, a merchant seaman and writer of numerous books on Great Lakes shipping, stated that if her cargo holds had watertight subdivisions, “ the Edmund Fitzgerald could have made it into Whitefish Bay. ” Frederick Stonehouse besides held that the miss of watertight bulkheads caused Edmund Fitzgerald to sink. He said :

The Great Lakes ore carrier is the most commercially effective vessel in the ship trade nowadays. But it ‘s nothing but a mechanize barge ! It ‘s the insecure commercial vessel afloat. It has about no watertight integrity. theoretically, a one-inch puncture in the cargo accommodate will sink it .

Stonehouse called on ship designers and builders to design lake carriers more like ships rather than “ motorized super-barges ” making the pursue comparison :

line this [ the Edmund Fitzgerald ] with the report of the SS Maumee, an oceangoing oil tanker that struck an iceberg near the South Pole recently. The collision tore a hole in the ship ‘s bow large adequate to drive a hand truck through, but the Maumee was able to travel halfway around the world to a repair yard, without difficulty, because she was fitted with watertight bulkheads .

After Edmund Fitzgerald foundered, Great Lakes shipping companies were accused of valuing cargo payloads more than homo life sentence, since the vessel ‘s cargo restrain of 860,950 cubic feet ( 24,379 m3 ) had been divided by two non-watertight traverse “ riddle ” bulkheads. The NTSB Edmund Fitzgerald investigation concluded that Great Lakes freighters should be constructed with watertight bulkheads in their cargo holds. The USCG had proposed rules for watertight bulkheads in Great Lakes vessels a early as the slump of Daniel J. Morrell in 1966 and did so again after the sink of Edmund Fitzgerald, arguing that this would allow ships to make it to refuge or at least admit crew members to abandon embark in an orderly fashion. The LCA represented the Great Lakes fleet owners and was able to forestall watertight branch regulations by arguing that this would cause economic hardship for vessel operators. A few vessel operators have built Great Lakes ships with watertight subdivisions in the cargo holds since 1975, but most vessels operating on the lakes can not prevent flood of the stallion cargo cargo area area .

lack of orchestration [edit ]

A sonic depth finder was not required under USCG regulations, and Edmund Fitzgerald lacked one, evening though fathometers were available at the time of her sinking. alternatively, a bridge player lineage was the lone method acting Edmund Fitzgerald had to take astuteness soundings. The hand line consisted of a man of line knotted at measured intervals with a lead weight on the end. The line was thrown over the bow of the ship and the count of the knots measured the water depth. The NTSB investigation concluded that a sonic depth finder would have provided Edmund Fitzgerald extra navigational data and made her lupus erythematosus dependent on Arthur M. Anderson for navigational aid. Edmund Fitzgerald had no system to monitor the presence or sum of urine in her cargo contain, evening though there was always some award. The volume of the November 10 storm would have made it unmanageable, if not impossible, to access the hatches from the spar deck ( pack of cards over the cargo holds ). The USCG Marine Board found that flood of the hold could not have been assessed until the water reached the top of the taconite cargo. The NTSB investigation concluded that it would have been impossible to pump water from the hold when it was filled with bulk cargo. The Marine Board noted that because Edmund Fitzgerald lacked a draft-reading system, the crew had no way to determine whether the vessel had lost freeboard ( the level of a ship ‘s deck above the water ) .

Increased cargo lines, reduced freeboard [edit ]

The USCG increased Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s load line in 1969, 1971, and 1973 to allow 3 feet 3.25 inches ( 997 millimeter ) less minimal freeboard than Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s original design allowed in 1958. This think of that Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s deck was only 11.5 feet ( 3.5 meter ) above the urine when she faced 35-foot ( 11 thousand ) waves during the November 10 storm. Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes noted that this change allowed loading to 4,000 tons more than what Edmund Fitzgerald was designed to carry. Concerns regarding Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s keel-welding problem surfaced during the time the USCG started increasing her load line. This increase and the resultant decrease in freeboard decreased the vessel ‘s critical reserve buoyancy. Prior to the load-line increases she was said to be a “ good ride transport ” but afterwards Edmund Fitzgerald became a sluggish ship with slower response and recovery times. Captain McSorley said he did not like the action of a ship he described as a “ jiggle thing ” that scared him. Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s bow hooked to one side or the other in arduous seas without recovering and made a groaning sound not heard on other ships .

care [edit ]

NTSB investigators noted that Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s anterior groundings could have caused undetected damage that led to major structural failure during the storm, since Great Lakes vessels were normally drydocked for inspection merely once every five years. It was besides alleged that when compared to Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s previous captain ( Peter Pulcer ), McSorley did not keep up with act maintenance and did not confront the mates about getting the necessity work done. After August B. Herbel Jr., president of the american Society for Testing and Materials, examined photograph of the welds on Edmund Fitzgerald, he stated, “ the hull was just being held together with patching plates. ” other questions were raised as to why the USCG did not discover and take corrective action in its pre-November 1975 inspection of Edmund Fitzgerald, given that her brood coamings, gaskets, and clamps were ill maintained .

complacency [edit ]

On the black even of November 10, 1975, McSorley reported he had never seen bigger seas in his life. Paquette, master of Wilfred Sykes, out in the lapp ramp, said, “ I ‘ll tell anyone that it was a monster ocean washing solid body of water over the deck of every vessel out there. ” The USCG did not broadcast that all ships should seek safe anchorage until after 3:35 post meridiem on November 10, many hours after the weather was upgraded from a gale to a storm. McSorley was known as a “ fleshy upwind captain ” who “ ‘beat hell ‘ out of the Edmund Fitzgerald and ‘very rarely always hauled up for weather ‘ ”. Paquette held the opinion that negligence caused Edmund Fitzgerald to founder. He said, “ in my opinion, all the subsequent events rebel because ( McSorley ) kept pushing that transport and did n’t have adequate discipline in upwind prediction to use coarse sense and pick a route out of the worst of the wind instrument and seas. ” Paquette ‘s vessel was the inaugural to reach a discharge port after the November 10 ramp ; she was met by company attorneys who came aboard Sykes. He told them that Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s collapse was caused by negligence. Paquette was never asked to testify during the USCG or NTSB investigations. The NTSB probe noted that Great Lakes cargo vessels could normally avoid austere storms and called for the establishment of a limiting sea state of matter applicable to Great Lakes bulge cargo vessels. This would restrict the operation of vessels in sea states above the limiting measure. One concern was that shipping companies pressured the captains to deliver cargo as quickly and cheaply as possible regardless of bad weather. At the time of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s fall through, there was no evidence that any governmental regulative agency tried to control vessel motion in cruddy upwind despite the diachronic read that hundreds of Great Lakes vessels had been wrecked in storms. The USCG took the side that only the captain could decide when it was safe to sail. The USCG Marine Board issued the be conclusion :

The nature of Great Lakes ship, with shortstop voyages, much of the meter in very protected waters, frequently with the lapp routine from trip to trip, leads to complacency and an excessively optimistic attitude concerning the extreme weather conditions that can and do exist. The Marine Board feels that this attitude reflects itself at times in postponement of alimony and repairs, in failure to prepare by rights for heavy weather, and in the conviction that since refuges are near, safety is possible by “ running for it. ” While it is true that sailing conditions are effective during the summer temper, changes can occur abruptly, with hard storms and extreme weather and ocean conditions arising quickly. This tragic accident points out the want for all persons involved in Great Lakes shipping to foster increase awareness of the hazards which exist .

Mark Thompson countered that “ the Coast Guard laid bare [ its ] own complacency ” by blaming the sinking of Edmund Fitzgerald on industry-wide complacency since it had inspected Edmund Fitzgerald barely two weeks before she sank. The loss of Edmund Fitzgerald besides exposed the USCG ‘s lack of rescue capability on Lake Superior. Thompson said that ongoing budget cuts had limited the USCG ‘s ability to perform its historical functions. He further noted that USCG rescue vessels were improbable to reach the scene of an incidental on Lake Superior or Lake Huron within 6 to 12 hours of its occurrence .

Legal settlement [edit ]

Under maritime law, ships capitulation under the legal power of the admiralty courts of their ease up country. As Edmund Fitzgerald was sailing under the U.S. iris, even though she sank in alien ( canadian ) waters, she was subject to U.S. admiralty law. With a value of $ 24 million, Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s fiscal loss was the greatest in Great Lakes sailing history. In summation to the crew, 26,116 farseeing tons ( 29,250 short circuit tons ; 26,535 triiodothyronine ) of taconite dip along with the vessel. Two widows of crewmen filed a $ 1.5 million lawsuit against Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s owners, Northwestern Mutual, and its operators, Oglebay Norton Corporation, one week after she sank. An extra $ 2.1 million lawsuit was by and by filed. Oglebay Norton subsequently filed a petition in the U.S. District Court seeking to “ limit their liability to $ 817,920 in connection with early suits filed by families of crew members. ” The company paid recompense to surviving families about 12 months in promote of official findings of the probable lawsuit and on condition of inflict confidentiality agreements. Robert Hemming, a reporter and newspaper editor program, reasoned in his koran about Edmund Fitzgerald that the USCG ‘s conclusions “ were benign in placing blame on [ n ] either the company or the captain … [ and ] saved the Oglebay Norton from very expensive lawsuits by the families of the lost crowd. ”

subsequent changes to Great Lakes ship commit [edit ]

The USCG probe of Edmund Fitzgerald ‘s sink resulted in 15 recommendations regarding burden lines, weathertight integrity, search and rescue capability, lifesaving equipment, crew education, loading manuals, and providing information to masters of Great Lakes vessels. NTSB ‘s investigation resulted in 19 recommendations for the USCG, four recommendations for the American Bureau of Shipping, and two recommendations for NOAA. Of the official recommendations, the take after actions and USCG regulations were put in station :

- 1. In 1977, the USCG made it a requirement that all vessels of 1,600 gross register tons and over use depth finders.

- 2. Since 1980, survival suits have been required aboard ship in each crew member’s quarters and at their customary work station with strobe lights affixed to life jackets and survival suits.

- 3. A LORAN-C positioning system for navigation on the Great Lakes was implemented in 1980 and later replaced with Global Positioning System (GPS) in the 1990s.

- 4. Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs) are installed on all Great Lakes vessels for immediate and accurate location in event of a disaster.

- 5. Navigational charts for northeastern Lake Superior were improved for accuracy and greater detail.

- 6. NOAA revised its method for predicting wave heights.

- 7. The USCG rescinded the 1973 Load Line Regulation amendment that permitted reduced freeboard loadings.

- 8. The USCG began the annual pre-November inspection program recommended by the NTSB. “Coast Guard inspectors now board all U.S. ships during the fall to inspect hatch and vent closures and lifesaving equipment.”

Karl Bohnak, an Upper Peninsula meteorologist, covered the dip and storm in a book on local weather history. In this book, Joe Warren, a deckhand on Arthur M. Anderson during the November 10, 1975, storm, said that the storm changed the way things were done. He stated, “ After that, trust me, when a gale came up we dropped the hook [ anchor ]. We dropped the hook because they found out the big ones could sink. ” Mark Thompson wrote, “ Since the loss of the Fitz, some captains may be more prone to go to anchor, preferably than venturing out in a severe storm, but there are inactive excessively many who like to portray themselves as ‘heavy weather sailors. ‘ ”

Memorials [edit ]

Edmund Fitzgerald Memorial at Whitefish Point

Edmund Fitzgerald Memorial at Whitefish Point

Edmund Fitzgerald bow anchor on display at the Dossin Great Lakes Museum The day after the shipwreck, Mariners ‘ church in Detroit rang its bell 29 times ; once for each life lost. The church continued to hold an annual memorial, reading the names of the crewmen and ringing the church bell, until 2006 when the church service broadened its memorial ceremony to commemorate all lives lost on the Great Lakes. The embark ‘s bell was recovered from the crash on July 4, 1995. A replica engraved with the names of the 29 sailors who lost their lives replaced the original on the wreck. A legal document signed by 46 relatives of the dead person, officials of the Mariners ‘ church of Detroit and the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historic Society ( GLSHS ) “ donated the custodian and conservatorship ” of the chime to the GLSHS “ to be incorporated in a permanent wave memorial at whitefish Point, Michigan, to honor the memory of the 29 men of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald.” The terms of the legal agreement made the GLSHS responsible for maintaining the bell, and forbade it from selling or moving the bell or using it for commercial purposes. It provided for transferring the bell to the Mariners ‘ church service of Detroit if the terms were violated. An hubbub occurred in 1995 when a maintenance actor in St. Ignace, Michigan, refurbished the bell by stripping the protective coat applied by Michigan State University experts. The controversy continued when the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum tried to use the bell as a touring show in 1996. Relatives of the crew halted this move, objecting that the bell was being used as a “ travel trophy. ” As of 2005, the doorbell is on display in the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Whitefish Point near Paradise, Michigan. An anchor from Edmund Fitzgerald lost on an earlier trip was recovered from the Detroit River and is on expose at the Dossin Great Lakes Museum in Detroit, Michigan. The Dossin Great Lakes Museum besides hosts a doomed Mariners Remembrance event each year on the evening of November 10. Artifacts on display in the Steamship Valley Camp museum in Sault Ste. Marie, include two lifeboats, photos, a movie of Edmund Fitzgerald and commemorative models and paintings. Every November 10, the Split Rock Lighthouse in Silver Bay, Minnesota, emits a idle in respect of Edmund Fitzgerald. On August 8, 2007, along a outback shore of Lake Superior on the Keweenaw Peninsula, a Michigan kin discovered a alone life-saving ring that appeared to have come from Edmund Fitzgerald. It bore markings different from those of rings found at the wreck locate, and was thought to be a fraud. Later it was determined that the life resound was not from Edmund Fitzgerald, but had been lost by the owner, whose church father had made it as a personal memorial. The Royal Canadian Mint commemorated Edmund Fitzgerald in 2015 with a color flatware collector mint, with a side value of $ 20 .